Bessie Coleman was born on January 26, 1892. Her parents worked as sharecroppers in a small community outside Dallas, Texas, and as a child, she helped pick cotton in the fields.

Coleman excelled in her segregated elementary school but could only afford a single semester of college. In 1915, at the age of 23, she moved to Chicago and took jobs in a restaurant and as a manicurist. In the city, she became interested in flying after hearing stories from pilots who had returned from World War I.

Undeterred, Bessie sought advice from Robert S. Abbott, founder of The Chicago Defender. He encouraged her to pursue training abroad and, along with Jesse Binga, founder of the first privately owned bank for Black Americans, helped sponsor her trip to France. After studying French to prepare, she set out for Paris in November 1920.

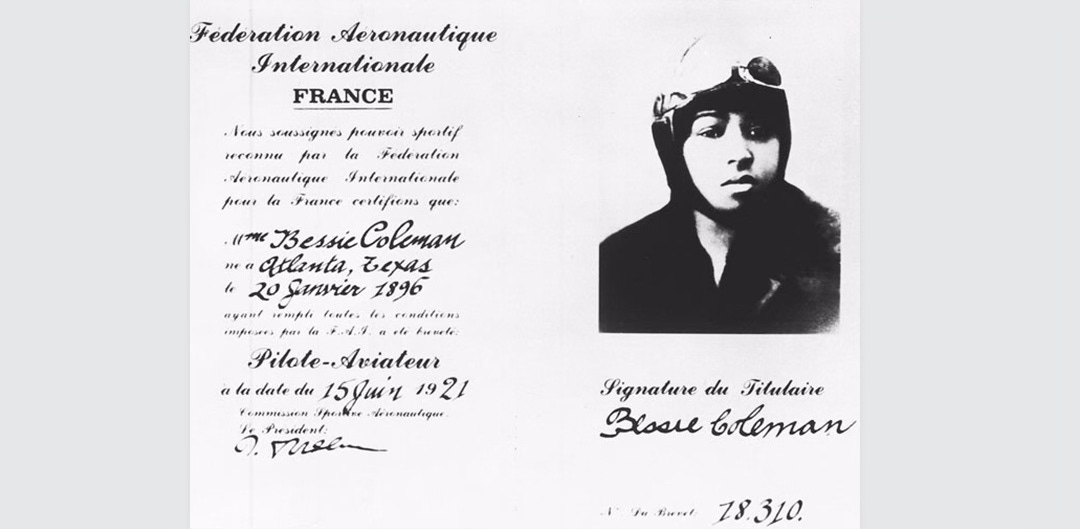

She joined the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale as a student, and in the summer of 1921, she became the first black woman to receive a pilot’s license. She is sometimes also considered the first Native American to become a pilot, as her father was partly of Native American descent.

Coleman received training from several prominent French and German pilots before returning to the United States, where she dazzled audiences as a stunt pilot, performing daring aerial tricks at airshows across the country. Known as Queen Bess, she drew thousands of spectators eager to witness her fearless feats.

But her performances were about more than entertainment; Coleman was committed to using her platform to challenge racial injustice. She famously refused to participate in shows that enforced segregation and dreamed of opening a flight school to train Black pilots.

Tragically, Bessie’s life was cut short. On April 30, 1926, her plane suffered a mechanical failure during a test flight. Without a seatbelt, she was thrown from the cockpit and fell to her death at just 34 years old.

Though her life ended far too soon, Bessie Coleman’s legacy endured. She broke barriers and inspired generations of Black pilots and women in aviation. She paved the way for future pioneers—including astronauts—who followed in her footsteps.

Further reading: Queen Bess: Daredevil Aviator by Doris L. Rich (1993) and ”Black Birds in the Sky: The Legacies of Bessie Coleman and Dr. Mae Jemison" by Kim Creasman in The Journal of Negro History (vol. 82, nr. 1, 1997).