Mali, Mansa Musa & The River of Gold

Facts and misconceptions about a legendary West African empire

It was a place where some believed valuable minerals grew in the ground and were picked as plants. An immense empire serving as a center of trade and religion, supplying Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East with much-coveted gold.

But it was also a place that may have inspired Europeans to venture further out into the seas than ever before, with consequences no one could have imagined. This is the story of Mansa Musa and the Mali Empire.

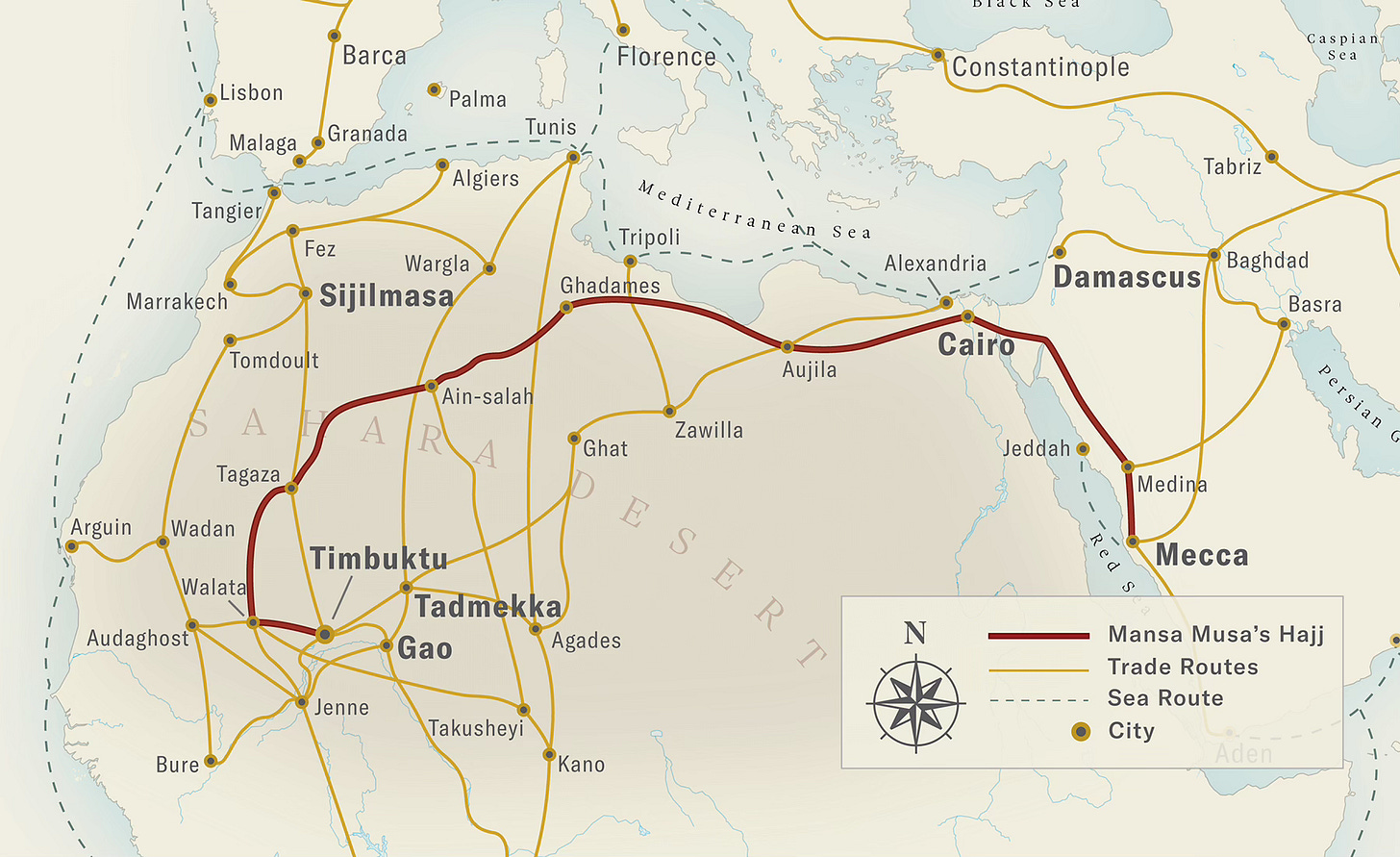

It must have looked like a mirage. The year was 1324, and a spectacle that warped the mind emerged from the vast dunes. A grand procession of horses, camels, and people snaked through the desert. Above them fluttered large red flags adorned with golden symbols.

Up to 60,000 men were part of the caravan, ranging from soldiers and officials to servants and enslaved people. 500 enslaved each carried a rod of pure gold, weighing 4 pounds or almost 2 kilos each, while the many camels each had loads of gold dust weighing over 220 pounds or 100 kilos. Leading this opulent display, a man of regal allure rode amidst the soldiers.

Accounts of the time describe him as youthful and handsome, with brown skin and a "pleasant face." His name was Mansa Musa, the revered leader of Mali, the grandest empire Africa had ever witnessed.

While this grand caravan was, in fact, a Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca, it also served a different purpose. By making the journey so lavishly, Mansa Musa was about to announce the Mali Empire as a new force to be reckoned with on the international stage.

Mansa Musa couldn't have known that this expedition would etch an indelible mark in the annals of African history. The staggering wealth he displayed captivated the world, painting Mali as a mythical realm where a river of gold flowed.

It also stirred inquisitive minds and ignited ambitious schemes. The allure of the gold Mansa Musa scattered prompted a natural curiosity: What other untold riches lay hidden in the depths of Africa beyond the immense expanse of the Sahara Desert? And what was the easiest route to seize those treasures?

This is a common way of describing Mansa Musa's pilgrimage. But the truth is there are several different versions of this tale. Historical events, especially ones as old as these, are rarely as straightforward as they first seem.

But before delving deeper into Mansa Musa's motivations for his pilgrimage, the different accounts of it, and the far-reaching consequences it bore, let us rewind the tape of time to show how Mali was part of a larger pattern. A pattern where West African kingdoms rose, expanded across enormous territories, and then collapsed.

Ancient Ghana

The banks of the middle Niger River, the part where it bends in a huge arc and flows through present-day Mali and Niger, is a region steeped in ancient history, where communities have flourished for thousands of years. Mema, one of the oldest settlements, may have been populated as early as the 3800s BCE. Archaeological excavations indicate that other distinctive communities, such as Dia and Djenné-Djeno, followed it.

The bustling settlement of Djenné-Djeno, in particular, played a vital role in the trans-Saharan trade between North and West Africa. Glass beads from distant Southeast Asia have been found in its ruins—a testament to the extent of ancient trade networks.

A limited and irregular trade between North and West Africa had been going on long before, but between 100 BCE and 100 CE, the camel was introduced into North Africa from the Arabian Peninsula, first in Egypt and then slowly over the rest of the region. These resilient beasts of burden would ignite a new era of trade and exploration and forever alter the dynamics of commerce.

With their ability to bear heavier loads than horses and donkeys and traverse inhospitable terrains, camels became the lifeblood of extensive trading expeditions. Devoid of hooves, they have large rounded feet with two toes, preventing them from sinking into the sand and enabling them to move through the soft or shifting ground. And with their humps storing fat reserves, they can go without water for a week. They were perfect for the Sahara.

Leading these expeditions were often nomadic peoples, traditionally known in the West as Berbers. This term has stirred controversy and is now viewed by many as derogatory. Rightfully proud of their heritage, these indigenous North Africans prefer to be called Amazigh, which translates to "free men."

Even after Arab Muslims conquered all of North Africa in the 7th and 8th centuries, the nomads' presence endured. These wanderers, masters of the desert's secrets, continued to wield their expertise as indispensable guides.

The caravans could be composed of up to 2000 camels. These caravans embarked on arduous journeys through scorching heat, relentless sandstorms, lurking bandits, and treacherously shifting dunes. They moved via several routes from oasis to oasis, seeking shelter in the shade and filling their water reservoirs. Control of the oases – politically and militarily – was paramount as they often provided control over the entire trade route. And with trade flourishing, these routes became veritable treasure troves.

The exhausting and dangerous journey through the desert spanned two to three grueling months. Eventually, the expeditions reached their ultimate destination—the so-called Sahel. The word comes from the Arabic "Sahil," meaning "coast." It refers to the belt stretching from Senegal in the west to Sudan in the east, marking the Sahara's transition to savannah and grasslands.

In the eyes of these traders and travelers, the desert was like a boundless sea, where camels played the role of sturdy vessels, and the oases became their coveted harbors.

Here, on the southern fringes of the desert, several kingdoms and communities awaited, ready to engage in trade. Among them, Gao in present-day Mali and Kanem in present-day Chad stood as thriving centers of commerce. The Arabs called this region bilal al Sudan, meaning the land of the blacks.

Salt emerged as a prized commodity. It was scarce in sub-Saharan Africa yet essential for preserving food—a property of almost immeasurable value. Conversely, the Arab traders from the north were captivated by ivory and, above all, gold. But trade in humans – enslaved people – also took place and grew in popularity over time. It is a subject I will return to in later articles.

Ghana was one of the most famous kingdoms the Arabs from the north traded with. Ghana extended its influence from the southeastern parts of present-day Mauritania to the lands of western Mali. As such, this historical kingdom of Ghana should not be conflated with the modern nation bearing the same name.

According to oral tradition, historic Ghana was founded by the Soninke people as early as the 4th century CE. The Soninke, alongside other groups like the Mandinka, Bambara, and Vai, form a cultural and linguistic group collectively known as the Mande people. They are found across large parts of West Africa.

Ghana's strategic location in the Sahel belt transformed it into a bustling crossroads, connecting the north and south. A medieval Arab writer, Al-Hamdani, claimed that Ghana boasted the world's most precious gold mines.

With vast quantities of salt procured, Ghana sold the surplus to others. Carried by camels, then passed along to donkeys and people, these prized blocks of salt embarked on a journey further south, venturing deeper into the lush forests of West Africa.

There, the scarcity of salt transformed it into a treasure of immense worth, multiplying its value manifold. From these bountiful regions, Ghana imported gold, which it then dispatched northward. Whispers of the kingdom's golden riches echoed far and wide. In the 9th century, the Persian historian Ibn al-Faqih wrote about how he imagined the gold production process.

"In the country of Ghana, gold grows in the sand as carrots do and is plucked at sunrise."

In the 11th century, the city that reigned as Ghana's capital, potentially the ruins of Koumbi Saleh in present-day Mauritania, existed as a divided city. It was a tale of two worlds, intertwined yet distinct.

On one side, the dense quarters thrived with Muslim inhabitants—merchants traversed from the north alongside Black African locals who embraced the faith. There were vibrant markets, imams, and twelve mosques. Wells provided fresh water, sustained the population, and nurtured their crops.

In the other part of town dwelled those who remained loyal to the non-Muslim king of Ghana. Here, the population lived in houses of stone and wood, while the king and his court lived in dome-shaped buildings inside a large stone wall.

Parts of the elite had gold jewelry woven into their hair, a testament to their status and opulence. This district also housed the spiritual leaders of the indigenous religions, and they kept watch over a sacred grove closed from the curious eyes of visitors.

About 10 kilometers, or 6 miles, separated the city's two parts, and smaller settlements bridged the gap. This arrangement allowed the groups to live in harmony without risking offending each other with their customs.

Occasionally, members of Ghana's native population would embrace Islam, yet they often retained parts of their traditional beliefs, merging the two. Notably, the court of the Ghanaian king included numerous Muslims, ranging from translators to advisors and treasurers, a testament to the growing influence of Islam within the kingdom.

The name "Ghana" was believed to be the title of the country's ruler. At the same time, the population themselves referred to their land as Wagadu. It is from this kingdom that the modern nation of Ghana derived its inspiration when it surfaced as an independent state in 1957.

The Arab historian al-Bakrī was born in the 11th century in Al-Andalus, the name the Muslims gave to the Iberian Peninsula, which they then controlled. According to him, Ghana had a matrilineal line of succession – meaning that the king's son did not inherit the throne but the king's sister's son.

This arrangement was founded on the king's perpetual uncertainty about his paternity. In contrast, the noble blood coursing through the veins of the sister's children held undeniable legitimacy in the eyes of the realm, as she alone had given birth to them.

Ghana was a military might, once commanding a formidable army of 200,000 men, which it used to subdue other kingdoms and societies. But in the 1070s, Ghana's power began to decline, coinciding with the rise of the Almoravids, a Muslim dynasty from North Africa.

Historians remain divided on the exact fate of Ghana. Some assert that the Almoravids forcefully conquered the kingdom. Others posit that Ghana succumbed to its influence through alternative means. However, Ghana persisted for several centuries, witnessing a gradual embrace of Islam among its populace.

Nevertheless, the days of Ghana as an imperial power were over.

The Imperial Cycle

By its very nature, an empire involves subjugating other states and peoples through military prowess, trade, or political maneuvering. At times, ruling over a diverse array of people with distinct languages, gods, and cultural traditions can be relatively frictionless. Yet, more often than not, empires embody inherent contradictions that can be managed during times of strength.

However, those contradictions tend to erupt when an empire weakens due to succession disputes, feeble leadership, environmental shifts, economic crises, or external threats. The once somewhat united fabric begins to fray. Perhaps one of the once-independent states yearns for autonomy once more, successfully breaking free. Others may join in, fueled by a shared yearning for self-governance. And so, the empire crumbles, fragmenting into smaller, self-determining regions,

Until one of these smaller kingdoms begins to subjugate its neighboring countries again, expanding at the expense of the others. And thus, the cycle of empire starts anew.

West Africa's history is replete with such stories of kingdoms rising and falling. With Ghana's waning might, a power vacuum emerged—a void eventually filled by the Sosso, another prominent Mande people and kingdom. Once a part of Ghana's empire, the Sosso now reveled in newfound independence, nurturing aspirations of grandeur and expansion.

The griot is a crucial figure in West African history. These master storytellers, also known as jali, djeli, or gewel, are poets, praise singers, storytellers, historians, and musicians. Through these people, the oral tradition has been preserved and told over the generations for several hundred years, always with instruments in hand, such as the kora or the balafon.

Sosso's most famous leader was a king named Soumaoro Kanté, who lived in the early 1200s. According to oral tradition, he was a tyrannical ruler. The stories of the griots portray him as a malevolent sorcerer and, in some versions, as an almost demonic force preying on innocent maidens. He conquered several neighboring kingdoms and subjected their people to harassment, exorbitant taxes, and violence.

In the Mali of the Mandinka people – one of the kingdoms forced to obey Sosso – the local leader had received a seer. The seer foretold that the leader would marry a disfigured or unattractive woman who would bear a son destined for great kingship. The problem was that this leader was already married to another woman and already had a son.

Yet, as fate would have it, he encountered a woman who perfectly matched the seer's description, the prophecy resonating within his mind. Thus, he wed her. Their son, Sundiata, was born weak and infirm and had trouble walking as he grew older. During his formative years, he endured relentless mockery from his father's first wife and son.

Sundiata's life shifted when his father passed away, as his father's wishes for Sundiata to become the new leader were disregarded. Instead, his older half-brother, born of his father's first wife, seized the throne. Due to continued harassment and threats, Sundiata was finally forced to seek refuge in the neighboring land of Mema.

But a remarkable transformation occurred in Mema. According to legend, Sundiata became strong as a lion and a skilled warrior and hunter.

At the same time, the expansion of the Kingdom of Sosso continued with Soumaoro Kanté at the head. Desperate and at the brink of despair, the people of Mali covertly dispatched an emissary to the exiled Sundiata, beseeching his return. Responding to their pleas, Sundiata rallied a coalition of clans and smaller kingdoms. In a climactic battle in 1235, they triumphed over Kanté and his bloodthirsty horde.

Following their victory, Sundiata and the leaders of the allied clans convened during a ceremony in the town of Kangaba. In exchange for granting these leaders their own realms to govern, they acknowledged Sundiata as their supreme ruler. They then ratified the Kouroukan Fouga—an early constitution. By uniting these clans, Sundiata created the foundation of the new West African superpower—the Mali Empire.

The Rise of Imperial Mali

This tale, The Epic of Sundiata, is a national epic. As an oral tradition, multiple versions exist, with their own unique rendition.

By all accounts, Sundiata Keita was probably not a Muslim. Or if he was, he doesn't appear to have been profoundly devout. However, in later iterations of the oral legend, the Keita dynasty—the ruling family of the Mali Kingdom—claims descent from Bilal ibn Rabah, a Black man from present-day Ethiopia, who was one of the earliest followers of the Prophet Muhammad and Islam's first muezzin: the person who calls to the daily prayer.

Establishing connections with esteemed early Muslims was a typical means for West African leaders to solidify their legitimacy, especially during Islam's rapid rise and spread in the region.

Regardless of how Muslim Sundiata Keita really was, it's clear that Mali, as a kingdom, increasingly embraced Islam. Conversion held clear advantages. It fostered closer ties with Muslim traders venturing from the north. It offered protection against enslavement, as it was forbidden to enslave fellow Muslims.

At the beginning of the 14th century, European ships had yet to chart the West African coastline. So, to access the region's abundant gold reserves, Europeans had to go through the Muslims. After all, the Muslims dominated the trans-Saharan trade, the routes that gradually transported the precious metal northward.

Like ancient Ghana once did, the Mali Kingdom emerged as a hub within this network. Mali boasted copper mines, exchanging this valuable resource, along with other metals, leather, cotton, and enslaved people, for the copious amounts of gold found in the southern reaches of West Africa. Once the gold was acquired, Mali transported the surplus further north, trading it with North Africa, the Middle East, and Europe. Additionally, kola nuts were a highly sought-after commodity Mali imported from the south.

The Mali Empire peaked during the reign of Mansa Musa, a descendant of Sundiata Keita. "Mansa" is not a first name; it's a title commonly translated to "king," "emperor," or "chief."

Mansa Musa's birth date remains evasive, but he ascended to the throne in 1312. Musa was a devout Muslim. It is said that whoever sought an audience with him had to sprinkle sand over his head and shoulders to show reverence and that Mansa Musa never spoke when he made public appearances. Instead, he communicated through whispers, entrusting a spokesperson to echo his voice to the world.

Mansa Musa's unwavering faith ignited his most renowned act: the pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324. In his acclaimed book African Dominion, the American historian Michael A. Gomez summarizes the various accounts of how much gold Mansa Musa brought with him on the journey. He arrives at the equivalent of 16 metric tons of gold.

To put that into perspective, it's estimated that only slightly over 200,000 metric tons of gold have been mined throughout history. Startlingly, more than half of that amount has been mined only since the 1950s. So the fact that Mansa Musa, on a single occasion, brought 16 metric tons of gold with him is a staggering number. It testifies to the colossal impact he wanted to make on the world around him.

However impressive these numbers are, it's a good idea to remember that much of the information about Mansa Musa and his pilgrimage hinges on conjecture. As mentioned previously, there are several accounts of this pilgrimage, many of which were written long afterward and shaped by the writer's agenda, experience, and bias. A medieval chronicler may claim that the pilgrimage comprised 20,000, 30,000, 60,000, or 100,000 people. But there's no way for that chronicler to accurately know how large Mansa Musa's entourage was. It's best not to take any of these numbers literally.

Here's another disclaimer:

Sometimes, when you read or talk about pre-colonial African history, there's a tendency to glorify the kingdoms and empires of that time. It's understandable, especially since we've all been fed the myth that Africa was this wild and uncivilized place with no kingdoms and empires. It makes sense, then, why some people want to elevate this pre-colonial period and are almost nostalgic about the time when "we" used to be kings and queens and emperors and whatnot.

But empires rarely form peacefully. By their very nature, they are products of violence, war, and conquest. And, of course, that's true for empires in Africa, just like it's true for empires elsewhere in the world.

To avoid the trap of uncritically ingesting information about what these "great men of history" have achieved, it's worth remembering that empires are complex. They're not solely "bad." But they're not exclusively "good" either, just because they existed in Africa.

As legend has it, Mansa Musa's generosity knew no bounds during his monumental pilgrimage. He showered gold upon dignitaries, hosts, representatives of mosques, and even ordinary people and the impoverished.

His liberality is said to have caused a ten-year dip in the value of gold in Cairo, the Egyptian city he visited on his way to Mecca. This astonishing display of wealth has led many media outlets, from Time Magazine to the BBC, along with numerous blogs, podcasts, and Instagram accounts, to crown Mansa Musa as the" richest man in history."

However, most historians caution against embracing such claims. Calculating wealth over nearly 700 years becomes daunting due to inflation, the multitude of parameters involved, and the differences in what constitutes wealth. Most argue that giving such a title to anyone in history is impossible.

Personally, I don't know how much that title really matters. What remains undeniable is that Mansa Musa's affluence was extraordinary. And that is interesting enough to note, especially given the Western myth that for so long painted sub-Saharan Africa as a place completely lacking in civilization and prosperity.

According to historian Michael A. Gomez, the opulence Mansa Musa showcased during his trip served to present Mali as a prestigious kingdom and to silence any skeptics questioning his legitimacy as the rightful ruler. Because there were, and are, uncertainties surrounding the circumstances of his ascension to the throne.

Many written sources about Mansa Musa are foreign and come from famous Muslim explorers and historians of the time, such as Ibn Khaldun, Ibn Battuta, and al-Umari. The indigenous oral sources are pretty silent about Mansa Musa, which is conspicuous since he played such a pivotal role in the golden age of Mali. This silence could hint at a quiet protest against his claim to power.

The pilgrimage to Mecca may also have been motivated by a desire to forge stronger connections with the Muslim world. This could be a path to protection and lucrative trade opportunities. Perhaps Mansa Musa hoped to attract foreign visitors and even more traders to Mali by projecting the kingdom as a land full of prosperity and abundance.

However, an often underrated reason for the pilgrimage was that completing it would solidify his right to rule back home. It was a theatre for local audiences, too.

In Cairo, Mansa Musa was received by the Egyptian Sultan an-Nasir Muhammad, and the contemporary sources tell slightly different versions of how the meeting took place. According to some sources, Mansa Musa gifted the Sultan 50,000 gold coins while receiving horses, camels, and provisions in return. The encounter seemingly radiated warmth and friendship.

Yet, records also hint at the power dynamics at play, with expectations for guests to kneel before the Sultan and kiss the ground. Mansa Musa defiantly refused, proclaiming his devotion to God alone. In certain versions of the tale, the two leaders engaged in a lengthy conversation seated side by side. In others, Mansa Musa was forced to stand—an exercise of power by the Sultan.

Regardless, the meeting ultimately took place. Mansa Musa stayed several months in Cairo before proceeding to Mecca and Medina, where he paid homage at the tomb of the Prophet Muhammad. The extravagant expenditures during the journey were so substantial that Mansa Musa had to borrow funds to finance his return from Cairo to Mali. Again, while his wealth was enormous, it was not infinite.

Mansa Musa wasn't the first West African ruler to complete the pilgrimage. But he did it more lavishly than anyone before him. In some ways, his extraordinary expedition literally put Mali on the map.

A few decades later, he was immortalized in the detailed Catalan world map of 1375. Resplendent in his regal attire, Mansa Musa sits on a throne, donning a golden crown. In one hand, he's brandishing a golden scepter, while the other hand is extending a gleaming golden nugget toward a camel rider emerging from a distant desert camp. The markings on the map trace the trade routes, traversing the Sahara, spanning the Mediterranean, and reaching the Iberian Peninsula—modern-day Spain and Portugal.

In A Fistful of Shells: West Africa from the Rise of the Slave Trade to the Age of Revolution, the British historian Toby Green comments on the map. He writes that the vivid depiction of Mansa Musa reflected how Europeans of the late 14th century perceived the trans-Saharan trade, with Mali's control over gold becoming the hallmark of the kingdom from a European perspective.

Another intriguing aspect of Musa's pilgrimage was that it reached the Middle East not long before firearms became common in that region. Had he gotten there a while later, he might have had the opportunity to acquire them, something that could have given Mali an even greater advantage over its neighbors and fundamentally altered the empire's destiny.

Upon Mansa Musa's return to West Africa, his reputation soared to new heights due to his pilgrimage. The ancient Gao and Timbuktu trading cities in present-day Mali had been incorporated into his empire. He brought renowned Muslim scholars and architects from his journey and had one of them design the Djingareyber Mosque, which, in a rebuilt form, still serves as a landmark in Timbuktu.

Musa also had a royal palace built. Timbuktu later developed into a bustling trade hub that attracted visitors from far-flung lands like Morocco and Egypt.

Aware of it or not, Mansa Musa was laying the foundation for the future emergence of Timbuktu as a prominent center of Muslim scholarship. During their golden age, the Djingareyber, Sankore, and Sidi Yahya Mosques became institutions of Islamic studies, welcoming over 20,000 students.

Mansa Musa's pilgrimage to Mecca is the single most famous event in the history of the Mali Empire. But there is another story: less known but just as fascinating. A tale about Mansa Musa's predecessor, a man obsessed with crossing the Atlantic.

The Malian Quest to Cross the Atlantic

Our only glimpse into this story is brought to us by the Arab historian al-Umari, born in Damascus in 1300. In his writings, al-Umari recounts a conversation between Mansa Musa and his host in Cairo, the governor of a district known as Old Cairo. Inquisitive about Mansa Musa's rise to power, the governor posed a question that unraveled a remarkable secret.

According to al-Umari, Mansa Musa revealed that he assumed the throne when his predecessor embarked on a daring expedition to seek the "furthest limit of the Atlantic Ocean."

As the story goes, this mysterious leader dispatched 300 ships laden with sailors, provisions, and precious gold from the shores of West Africa.

In many modern renderings, for example, on various sites and Instagram accounts, it is often claimed that the predecessor was Abu Bakr II. But a mansa of that name has never ruled Mali. The mistake is probably due to an incorrect translation. In fact, the predecessor was a king known as Mansa Qu, or his son Muhammad ibn Q.

Only one of the vessels returned. All the others had disappeared, and the lone surviving captain recounted a harrowing tale. After traveling on the open sea, the expedition encountered and succumbed to a "river with a powerful current."

While many may have been deterred by the loss of hundreds of ships, Mansa Musa's predecessor remained undeterred, convinced that the captain had misunderstood, was exaggerating, or simply wasn't competent enough.

Seemingly driven by an unyielding spirit, the predecessor did it himself. Embarking on a new expedition, led by his hand, he endeavored to complete the journey over the uncharted Atlantic.

According to al-Umari, the new expedition supposedly consisted of 2,000 ships. This time, none of the boats returned. Mansa Musa stepped forward to claim the throne as the Mali Empire found itself without a ruler.

In African Dominion, Michael A. Gomez writes that this fanciful narrative cannot be immediately dismissed. The territory of Mali had, by this time, expanded enormously and reached the shores of the Atlantic in present-day Senegal and The Gambia. Throughout history, it has been human nature to want to explore the unknown – what lies on the other side of an ocean, for example – and for Mali, it would've been natural in many ways to want to continue expanding its empire.

Gomez speculates that the "powerful current in the middle of the sea" may have referenced the mighty Canary Current. It flows south from Morocco to Senegal before merging with the North Equatorial Current and flowing west towards the Gulf of Mexico. It then merges into the Gulf Stream, which flows back towards Europe and North Africa. From there, the current flows south and begins the cycle again.

If the story was entirely made up – if the Mali Empire never even tried to cross the Atlantic – Gomez suggests that it would be strange that they knew of such a specific thing about the Atlantic's workings. He also points out that the large amounts of gold allegedly loaded aboard the boats indicate that the expedition may have had a commercial purpose. Mali's sailors hoped to find new trade partners or trade routes.

In Born in Blackness: Africa, Africans, and the Making of the Modern World, American journalist Howard W. French weaves a compelling narrative that intertwines with Gomez's theories. French contemplates the possibility that the ambitious sea voyage may have aimed to bypass North African intermediaries, reaching Southern Europe instead. With its immense wealth and strategic location, the Mali Empire may have sought to establish a direct trade connection with Europe.

However, as the tale unfolds, skepticism arises. Despite these exciting hypotheses, most things speak against the fact that the expeditions took place.

Al-Umari relied on secondhand accounts rather than personal encounters with Mansa Musa. And he penned his story many years after Musa visited Cairo.

Furthermore, the boats available to the Mali Empire then were likely ill-suited for transatlantic voyages. Although East Africa had long embraced sailing ships for Indian Ocean exploration, the West African region had yet to develop vessels of similar capabilities. Early European visitors along the West African coast during the century after Mansa Musa lived described canoes – enormous indeed – but more suited for rivers, lakes, and coastal navigation than transoceanic journeys. In the absence of evidence to the contrary, historians have assumed that the same types of canoes were also used in Musa's time.

The biggest argument for why this expedition might not have happened is that such a large project would've been mentioned elsewhere, in local oral tradition or other contemporary written sources. But al-Umari's writings are the only places where the story is mentioned. In addition, no archaeological findings have been made to prove that the trip, or even the preparations, really happened.

Nevertheless, the allure of the Mali Empire's mythical voyage continues to captivate the imagination. Despite the lack of evidence, some people argue that the journey not only took place but that the Malian ships arrived on the other side and thus "discovered" America.

Another possible theory is that Mansa Musa's grand tale may have been an elaborate cover to conceal a darker truth, as his path to power wasn't entirely straightforward.

His predecessor – the previously mentioned Mansa Qu or Muhammad ibn Q – came from another branch of the royal Keita family. Some historians speculate that Musa, driven by ambition, may have forcefully removed them to secure his reign. The tale of transatlantic expeditions could have been concocted as a smokescreen, masking the origins of his rise to power.

Yet, there's always the possibility that some combination could be true. Perhaps a first attempt at crossing the vast ocean happened, followed by a fabricated account of a subsequent venture. Maybe that could play a part in the indigenous oral traditions being curiously silent on Mansa Musa. But with the scarcity of sources, it's impossible to know.

A Crumbling Empire

Mansa Musa reigned over the sprawling Mali Empire during its golden age—but he was blissfully unaware that the majestic realm was slowly crumbling beneath the surface.

The order of succession, who replaces a regent on the throne, is a topic of perennial fascination. It has sparked discord, conflict, and war throughout history. In many patriarchal societies, the pressure to produce a male heir has been immense, as males have traditionally been favored when it comes to inheritance. In Sweden, where I live, we still have a monarchy, and it wasn't until 1980 that we embraced absolute cognatic primogeniture, allowing the firstborn child, regardless of gender, to ascend the throne.

If the lack of a male heir has sometimes been a problem among European royalty, parts of West Africa have faced a different predicament—the male heirs have been too many. In the Mali Empire, Islamic customs permitted up to four wives, each with the potential to bear sons. Add to that the mistresses and concubines who could also bear children. Andthe king's large family, including brothers, uncles, and cousins—all with potential aspirations of ruling one day.

This surplus of male heirs was a recipe for competition and quarrels. Compared to societies with simple and straightforward rules of succession, many West African kingdoms grappled with complicated and ambiguous regulations, leaving room for multiple claimants to the throne. The Mali Kingdom was no exception.

Mansa Musa's reign brought forth a quarter-century of stability and prosperity. However, upon his passing in 1337, his son Magha assumed power, only to be swiftly deposed by Musa's brother, Sulayman.

An age of political instability dawned, shrouding the kingdom in uncertainty. Sulayman's marriage to his cousin, the esteemed Qasa, endowed her with the status akin to a queen, and together they ruled.

Yet, as time passed, their relationship soured, and Sulayman's affections turned toward another woman unrelated to the royal lineage. Qasa was imprisoned or placed under house arrest, eliciting uproar from the nobility and the royal family— especially the women who rallied against this injustice. The protests persisted until Qasa hinted at Sulayman's permanent removal—a risky move that ultimately cost her support.

Sulayman's reign endured for over two decades, skillfully navigating the challenges to uphold the empire. By 1350, the Mali Empire stood as a colossal entity, stretching from its eastern borders near present-day Chad and Algeria to the southern reaches of Burkina Faso and Ivory Coast. To the west, its dominion extended as far as Senegal and The Gambia. It was a realm teeming with life, believed to have housed up to fifty million people.

But the death of Sulayman unleashed a storm of power struggles and rival claims to the throne. The reigns of the adversaries were short-lived, while the once-mighty army found itself divided and embroiled in internal strife.

From the south, the Mossi people started raiding. While in the west, the Wolof people rebelled and formed their own independent kingdom in what is now Senegal.

The Mali Empire had become too vast, too unruly. The failure to secure the land borders emboldened the kingdoms that made up the empire, and they began to break away one by one.

One of these kingdoms, or city-states, to rebel, was Gao in the 1430s. One of West Africa's oldest and most important trading cities, it once again became independent.

The imperial cycle proves true once more. A small kingdom at first, Gao quickly transformed under the formidable leadership of Sunni Ali, a warrior king with boundless ambitions. Gao expanded its dominion with each conquest, eventually blossoming into the enormous Songhai Empire. Unlike Mali, where the Mandinka people were in control, Songhai would become a more multi-ethnic project, growing into a state that dominated most of West Africa in the 16th century.

As the crumbling Mali Empire lost ground to the emerging Songhai, it staggered through the 16th century. Then, over the 17th century and gradually weakened by relentless challenges, the Mali Empire ceased to exist.

An Underrated Catalyst of Global Change?

Mansa Musa succeeded in his goal of projecting Mali as a mighty empire worthy of a place alongside other influential kingdoms of the Middle Ages. The idea of Mali as a place drenched in gold made the kingdom legendary in parts of Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East. Mali became associated with trade, wealth, and abundance for people in those regions.

But Mansa Musa's famed pilgrimage also attracted a different kind of attention. In the 15th century, just a few decades after Mansa Musa and his gold appeared on the Catalan world map, the Age of discovery began. It was a time when Western Europe went from being a relatively insignificant corner of the world to having its big breakthrough.

Traditionally, the search for a sea route to India has been cited as the impetus for this transformative period. In that version of events, Africa is reduced to a mere side track, a single big obstacle explorers had to go around to reach the final destination.

But in Born in Blackness, the author Howard W. French argues that exploring Africa – and tapping into the enormous riches that Mansa Musa displayed – was an end in itself.

Africa held allure and intrigue— it was a prize to be won. In the 15th century, Portuguese explorers set sail along the West African coast. The correspondence they left behind testifies to their attempts to contact a powerful king who ruled a kingdom called "Melli" further inland.

The writings and testimonies of the city of Timbuktu's prosperity also reached the shores of Europe, painting the town as a mythical realm. Well into the 19th century, the whispers of its unimaginable wealth lured expeditions sponsored by Britain and France to pursue the fabled "Eldorado of Africa." Little did they know that Timbuktu had long lost its prominence, its glorious days fading into the annals of history.

The Portuguese explorers in the 15th century couldn't have known it then, but Portugal's ventures along the African coast would irrevocably alter the course of human history. The world would never be the same again. And for Africa, a new dark chapter awaited. More on that in a future article.

Further reading:

Books:

Peoples and Empires of West Africa; West Africa in History, 1000–1800 by George Stride & Carolina Ifeka (1971)

Ancient and Mali by Nehemia Levtzion (1980)

In Search of Sunjata: The Mande Oral Epic as History, Literature and Performance by Ralph Austen (1999)

Corpus of Early Arabic Sources for West African History by Nehemia Levtzion & J.F.P. Hopkins (2000)

The History of Islam in Africa by Nehemia Levtzion & Randall L. Pouwels (2000)

Medieval West Africa: Views From Arab Scholars and Merchants by Nehemia Levtzion & Jay Spaulding (2003)

Empires of Medieval West Africa by David Conrad (2005)

Sundiata: An Epic of Old Mali by Djibril Tamsir Niane (2006)

A Cultural History of the Atlantic World, 1250–1820 by John K. Thornton (2012)

Beyond Timbuktu: An Intellectual History of Muslim West Africa by Ousmane Oumar Kane (2016)

African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa by Michael A. Gomez (2018)

A Fistful of Shells: West Africa from the Rise of the Slave Trade to the Age of Revolution by Toby Green (2019)

Born in Blackness: Africa, Africans, and the Making of the Modern World by Howard W. French (2021)

Scholarly articles:

"The Thirteenth- and Fourteenth-Century Kings of Mali" by Nehemia Levtzion in The Journal of African History (vol. 4, nr 3, 1963)

"The Age of Mansa Musa of Mali: Problems in Succession and Chronology" by Nawal Morcos Bell in The International Journal of African Historical Studies (vol. 5, nr 2, 1972)

"The Inland Niger Delta Before the Empire of Mali: Evidence from Jenne-Jeno" by Roderick J. McIntosh & Susan Keech McIntosh in The Journal of African History (vol. 22, nr 1, 1981)

"History, Oral Transmission and Structure in Ibn Khaldun's Chronology of Mali Rulers" by Ralph Austen & Jan Jansen in History in Africa (vol. 23, 1996)