The Humanitarian Crisis in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

And how it's connected to the minerals in our electronics

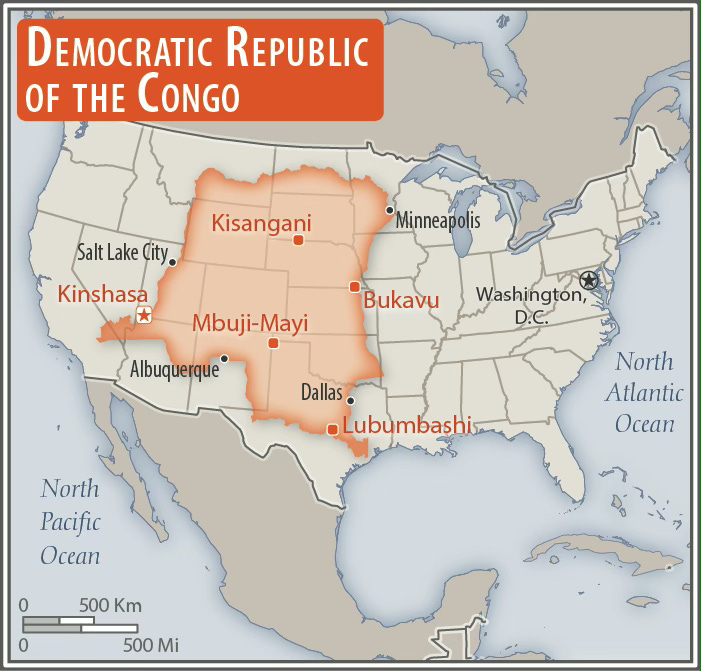

The humanitarian catastrophe in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) has taken another devastating turn in 2025. The M23 rebel group—backed by Rwanda—has seized control of Goma, a city of millions, forcing 400,000 people to flee in January alone.

The United Nations warns that 21 million Congolese need aid, while fears grow that Rwanda is orchestrating a de facto annexation of the mineral-rich region. Strategically located near the Rwandan border, Goma is a key transit hub for Congo's vast mineral wealth.

In late January, Congo's Foreign Minister, Thérèse Kayikwamba Wagner, alleged that Rwanda is no longer just funding the rebels but is now deploying its own troops to support them.

Rwanda—a key Western ally in Africa—has yet to deny her claims. Meanwhile, the conflict continues to exact a horrific toll on civilians, with reports of widespread killings and sexual abuse.

As the crisis escalates, Congo is calling on the international community to impose sanctions on Rwanda, urging swift action to end the war.

What's the background?

For almost 140 years, the Democratic Republic of the Congo has been one of the world's most crisis-stricken regions. This is despite, or rather because of, its enormous natural resources.

Congo has a wealth of minerals and raw materials that the world is absolutely clamoring for. It also has the world's second-largest rainforest, vast fertile lands, and impressive biodiversity. The potential for prosperity is enormous. But exploitation best sums up the last two centuries of Congo's history:

It began during the reign of Belgian King Leopold II at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries when up to ten million people were killed in a frenzied hunt for ivory and rubber.

The abuses continued with the Belgian state's apartheid-like colonization until 1960.

Dreams of freedom and democracy died with the Belgian-backed assassination of Congo's first prime minister, Patrice Lumumba, in 1961.

I have touched on all of these on my Instagram before and will write more extensively about them here in the future. But to keep this piece from becoming obscenely long, the story will begin with Mobutu, the man who took over from Lumumba.

The Great Plunderer

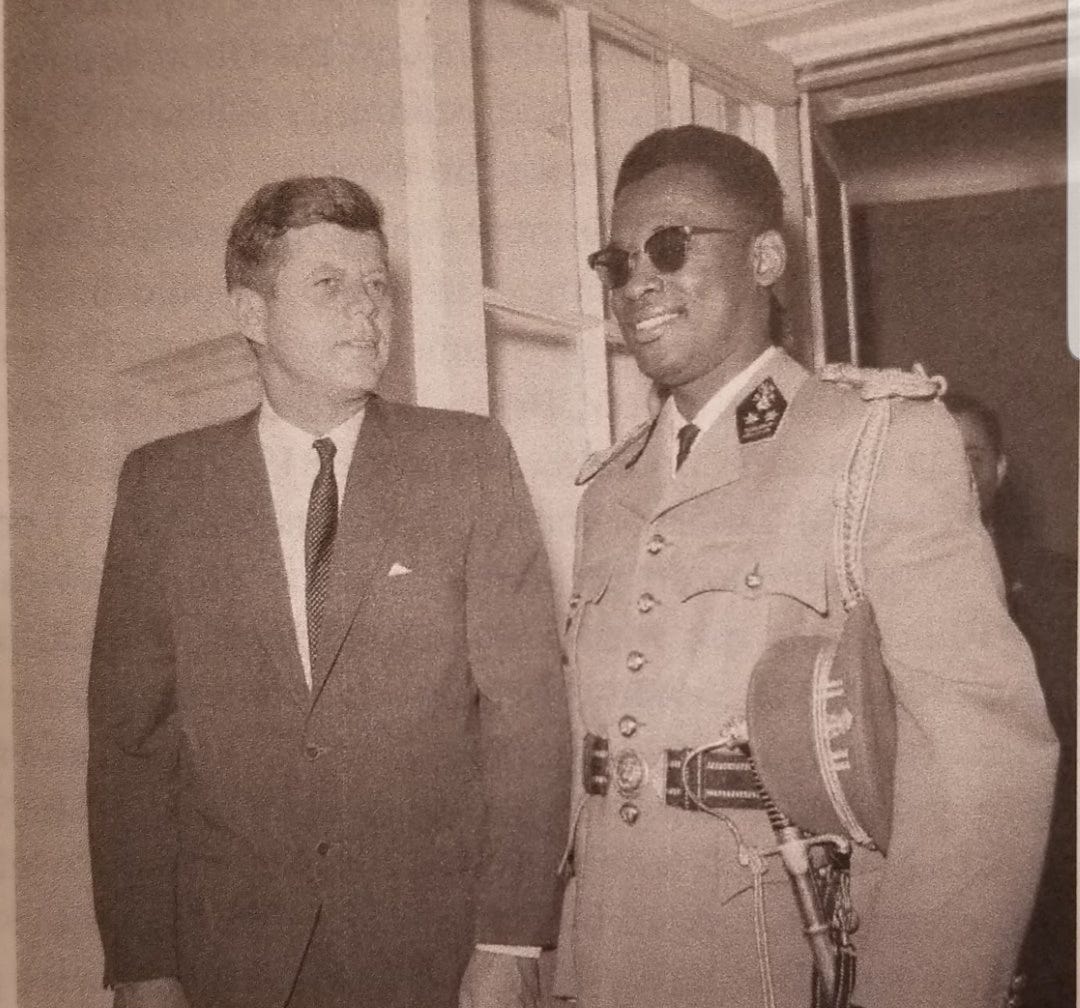

After the assassination of Patrice Lumumba in 1961, the Congo Crisis, which had characterized the country since independence the previous year, continued. The power struggle became bloodier and more intractable with each passing year.

Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, one of Lumumba's closest men, had been heavily involved in his assassination and now emerged as the country's leader in practice. In 1965, Mobutu formally took over in a military coup, highly unwilling to share power with anyone.

Mobutu had previously been supported by the CIA with weapons and funds, and he continued relying on the US after the coup. He dissolved parliament, suppressed his opponents, and founded the Mouvement Populaire de la Révolution—the country's only legal party. Politicians had ruined the country, he claimed, and restoring it was now up to him.

Progress was made initially. Mobutu's regime promised stability after so many years of conflict and division. Congo's immense natural resources, such as copper, cobalt, diamonds, and gold, helped grow the economy. The country became the subject of large amounts of foreign investment, and in the West, Mobutu was portrayed as a central figure in preventing the spread of communism in Africa.

Despite his involvement in the murder of Lumumba, Mobutu internally positioned himself as the one to carry on his legacy. Focused on emphasizing the country's genuineness, authenticité or Mobutism became a new state ideology—a way to, at least on the surface, shake off the colonial legacy and build a new national identity. In the process, Léopoldville, Stanleyville, and Élisabethville were renamed Kinshasa, Kisangani, and Lubumbashi.

In 1971, he gave the country the new name Zaire, which ironically had at times been the Portuguese name for the Congo River. They, in turn, had derived the name from the Kikongo word "nzere," which roughly translates to "river that swallows all rivers."

The following year, Joseph-Désiré Mobutu took the name Mobutu Sese Seko Nkuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga, which translates to "The all-powerful warrior who, because of his endurance and inflexible will to win, goes from conquest to conquest, leaving fire in his wake."

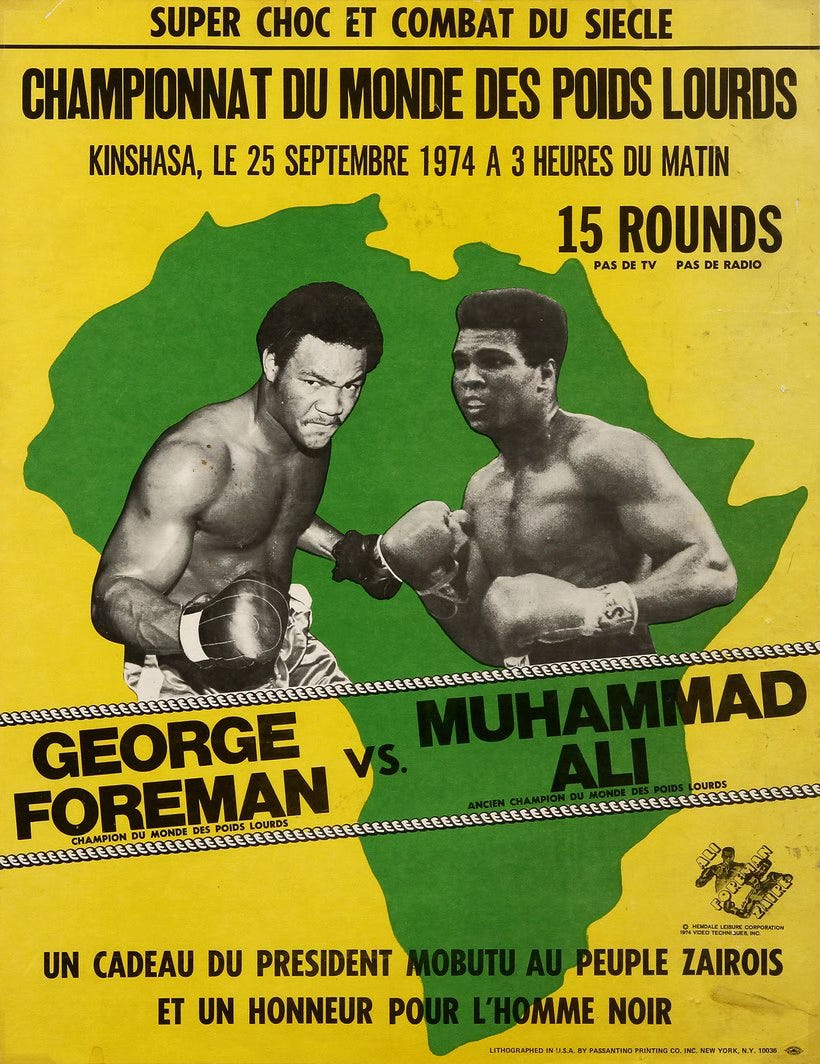

In 1974, in a massive PR campaign, the world heavyweight boxing championship match between George Foreman and Muhammad Ali was held in Kinshasa. The Rumble in the Jungle was one of the most remarkable sporting events of the 20th century and became a crown jewel of Mobutu's leadership of the still-young nation.

At the same time, he demonstrated rarely seen greed and narcissism. He cultivated a cult of personality in his classic outfit of thick-framed black glasses, cane, and leopard-skin hat. Government employees in Zaire wore pins with his portrait on them; television broadcasts began with an image of Mobutu descending from the heavens, and the public was implored to refer to him as the Messiah and the nation's father. Before the school day began, students were expected to dance in his honor.

Mobutu's legacy is his shameless deprivation of Zaire's economic potential. He took over countless foreign companies, but rather than nationalizing them, he distributed them among himself, his family, and allies, who plundered them of assets.

The central bank was used as his ATM, and he acquired extravagant apartments, villas, and office buildings worldwide. Along the Congo River, he coasted in his three-story luxury yacht, described as a floating palace, where he entertained politicians and corporate bigwigs.

Mobutu spent hundreds of millions of dollars turning the small village of Gbadolite into his paradise. He erected three palaces with artificial lakes, magnificent gardens, marble walls, and antique furniture.

In the Versailles of the Jungle, as the community came to be known, a school, a hospital, a nightclub, a shopping mall, a library, a fallout shelter, and an airport with a runway long enough for a Concorde were built. Among other things, he used the supersonic plane to go on spontaneous shopping trips to Paris.

Mobutu's fleecing of the country's assets was copied by his allies, who, as far as their power allowed, also abused their influence to enrich themselves. Zaire turned into a pure kleptocracy, where the rulers shamelessly exploited the country's resources for their own gain.

Meanwhile, Mobutu enjoyed extensive financial and military support from the West, mainly France and the United States, thanks mainly to his anti-Soviet line.

By the early eighties, Mobutu had amassed a fortune worth five billion dollars, making him one of the world's wealthiest men. All while the population's standard of living was continuously deteriorating.

Zaire in crisis

In the mid-70s, the price of copper, the country's most important export, plummeted. The early economic boom under Mobutu's leadership was now a thing of the past, and Zaire was on the verge of collapsing.

During the 1970s and 1980s, the colossal country became more like a collection of fragmented provinces than a cohesive nation. In many regions, roads stopped being maintained, telephone and postal service ceased, and the justice system crumpled.

Teachers went without salaries, hospitals were forced to close, and soldiers complained about non-payment. Political opposition existed, but Mobutu bought off those who could be purchased and imprisoned the rest.

By early 1990, Zaire's economy was in such bad shape that Mobutu agreed to allow other political parties. But he had no plans to relinquish control. Several of the new parties were formed by Mobutu's allies, and he fueled ethnic conflicts to turn groups against each other.

But Mobutu was increasingly under pressure. The fall of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War made his anti-communist line less valuable in the eyes of Western leaders. After counting on political, military, and financial support from the West for over 30 years, Mobutu was now left without.

At the same time, the economy declined even further. Inflation was over 8000%, and at the end of 1992, Mobutu introduced a new note of 5 million zaires. It was only worth the equivalent of 3 US dollars.

Mobutus was losing his grip on Zaire. But 1994's disastrous developments in neighboring Rwanda would spell his end.

How the Rwandan genocide toppled Zaire

(This topic will require a more detailed account in the future, but here's the quick version so you can see how it relates to Zaire/DRC.)

The Kingdom of Rwanda had existed in today's Rwanda since the 15th century when the Germans encountered it in 1894. Around the same time, battles for the throne broke out after the Rwandan king's death, facilitating German colonization.

Most of the population was Hutu, but historically, the Rwandan monarchy had been ruled by the Tutsi minority. Even so, the division was not strict: many Tutsi were farmers, and there were Hutu who belonged to the nobility.

However, the differences between the groups were magnified during the German colonization. Inspired by" scientific" racism, the Europeans claimed that the Tutsi belonged to a higher "race," which once upon a time had migrated in from outside and subjugated the Hutus. The idea was part of the Hamitic hypothesis, which claimed that all African civilization deemed worthy by Europeans had originated outside Africa and was created by Hamites – a subcategory of the Caucasian, or white, race. The myth took hold.

Belgium took over the colony after World War I and continued where Germany left off. In the 1930s, the Belgians introduced identity cards specifying the "race" of Rwandans, making movement between the groups impossible.

The opposition between the groups continued during decolonization. During the Rwandan revolution of 1959, the Tutsi monarchy was overthrown and replaced by a Hutu-dominated republic, which declared independence in 1962. Hundreds of thousands of Tutsis were forced to flee.

The coming decades were characterized by autocratic rule and Tutsi discrimination. And the early 90s were years of upheaval:

Tutsis in exile formed the Rwandan Patriotic From (RPF), returned, and sparked a civil war in 1990.

A ceasefire followed in 1993.

The ceasefire ended when Rwanda's president was assassinated in an as-yet-unsolved attack in 1994. The next day, everything erupted.

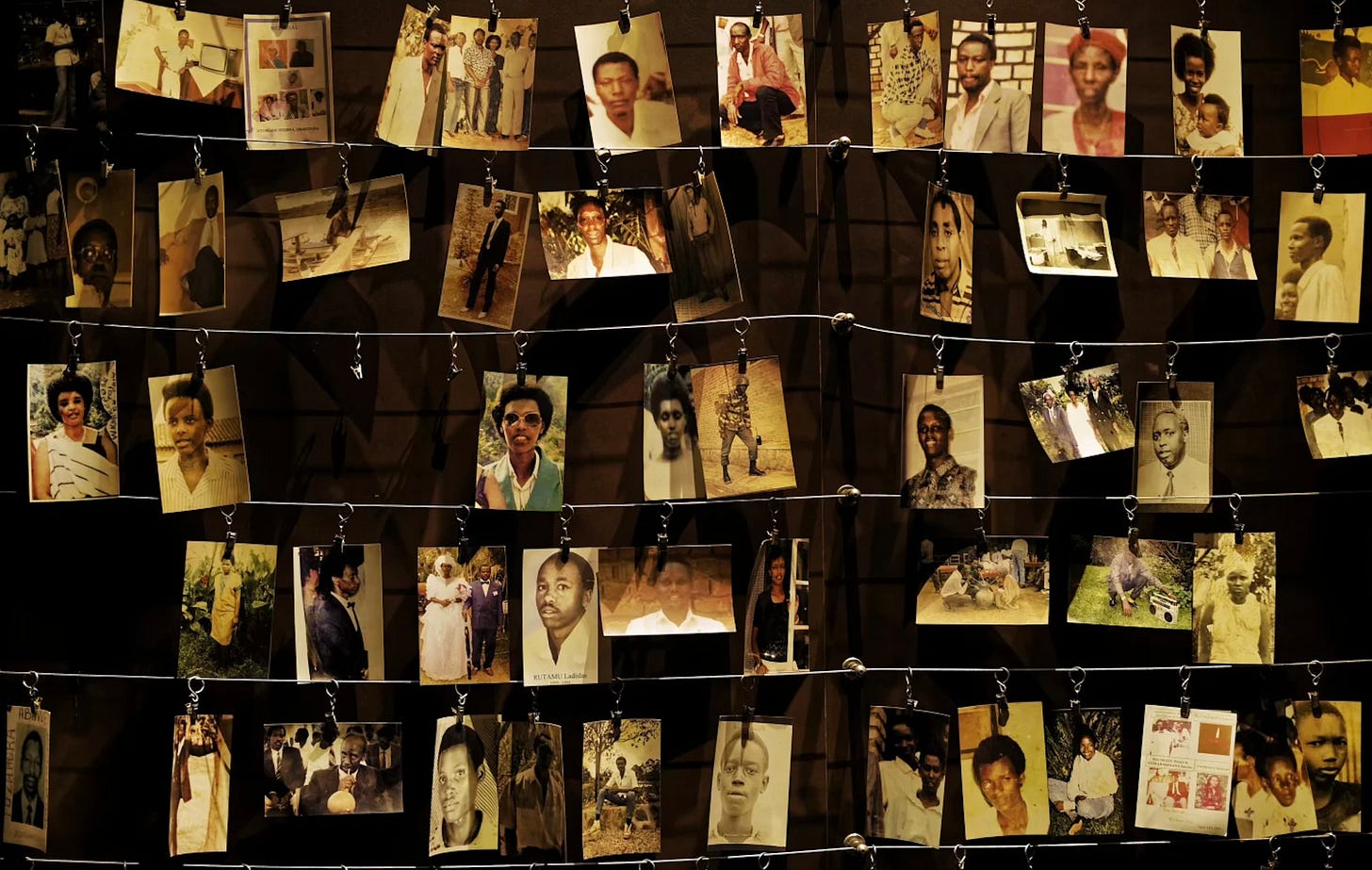

For a hundred days, Rwanda descended into an unfathomable nightmare. Between April and July 1994, mobs roamed from house to house, killing as many Tutsis as possible. Hutus who refused to take part in the slaughter, along with members of the Twa ethnic group, were also brutally killed.

Neighbors turned on neighbors. Teachers butchered their own students. Priests betrayed those seeking sanctuary in churches, delivering them to their executioners.

By the time the killing subsided, up to a million lives had been extinguished.

And through it all, the world stood by and watched.

For example, the Clinton administration initially prohibited officials from describing it as genocide to avoid pressure to intervene. Instead, the term "acts of genocide may have occurred" was preferred. French and Belgian forces that arrived only evacuated their own.

Several forces contributed to the world's shameful inaction as Rwanda descended into genocide:

Global news outlets were fixated on the O.J. Simpson murder case, choosing sensational headlines over the horrors unfolding in Rwanda.

The disastrous US intervention in Somalia just a year earlier made Western powers wary of getting entangled in another African conflict.

The United Nations, crippled by bureaucracy and indecision, proved ineffective.

Many governments dismissed the crisis as an "internal conflict," reluctant to involve themselves in a region they deemed strategically unimportant.

The RPF, determined to seize power, viewed peacekeeping troops as an obstacle to their military objectives and discouraged their presence.

Whatever the reason, the result was disastrous for those on the ground. French historian Gérard Prunier writes about how it could look when Western forces evacuated their citizens in his book The Rwanda Crisis: History of a Genocide:

"The hurried evacuation was a disgrace. Some Tutsi who had managed to board lorries heading for the airport were taken off the vehicles at militia roadblocks and slaughtered under the eyes of the French or Belgian soldiers who, obeying their orders, did not react. In other cases, the African partners in mixed-races couples were refused access on board; a tearful Russian woman married to a Tutsi pharmacist was not only forced to abandon her husband but had to plead to be allowed to take her half-cast children on the plane."

The killings only stopped when the Tutsi-dominated rebel group RPF defeated the government troops. The aftermath would bring Mobutu and Zaire down.

Paul Kagame’s Rise to Power

After defeating the government troops, the Tutsi-dominated RPF ended the Rwandan genocide. The RPF took power, and its leader, Paul Kagame, declared the civil war over.

A government of national unity was formed. Pasteur Bizimungu, a Hutu, became president, while Kagame, a Tutsi, became vice president. However, as commander of the army, Kagame held the real power.

When it became clear the RPF would win, scores of Hutus, fearing reprisals, had begun to flee. Entire communities were emptied. In the summer of 1994, over a million refugees moved across the border into eastern Zaire. There, they settled in overcrowded refugee camps. Several of the masterminds behind the genocide, as well as tens of thousands of militia members who carried out the actual killings, hid among the fleeing civilians.

The refugee crisis made headlines. The international community had ignored the genocide – it wouldn't repeat it with the impending humanitarian disaster. The West, the UN, and NGOs organized massive aid shipments.

But in the vast refugee camps, the Hutu militias and politicians who were behind the genocide quickly took power. They established a hierarchical system in which the old political and military elite controlled the distribution of aid shipments. They ensured their ranks had everything they needed while others were left without. Parts of the aid shipments were resold to finance the purchase of weapons. Ordinary Hutu civilians were threatened and forced to obey.

Ethnic conflicts had already marked eastern Zaire, and Tutsis were already living in the region. Under Mobutu's leadership, they had been increasingly discriminated against and were now portrayed as invaders. In the fall of 1996, the Tutsi were given a week to leave the country, a threat that breathed life into a resistance movement.

At the same time, from their refugee camps, the Hutu extremists, under the patronage of Mobutu, continued to plan for and carry out new acts of violence against the Tutsis. Kagame had enough. That fall, Rwandan soldiers crossed the border into Zaire. A major Central African war was now imminent.

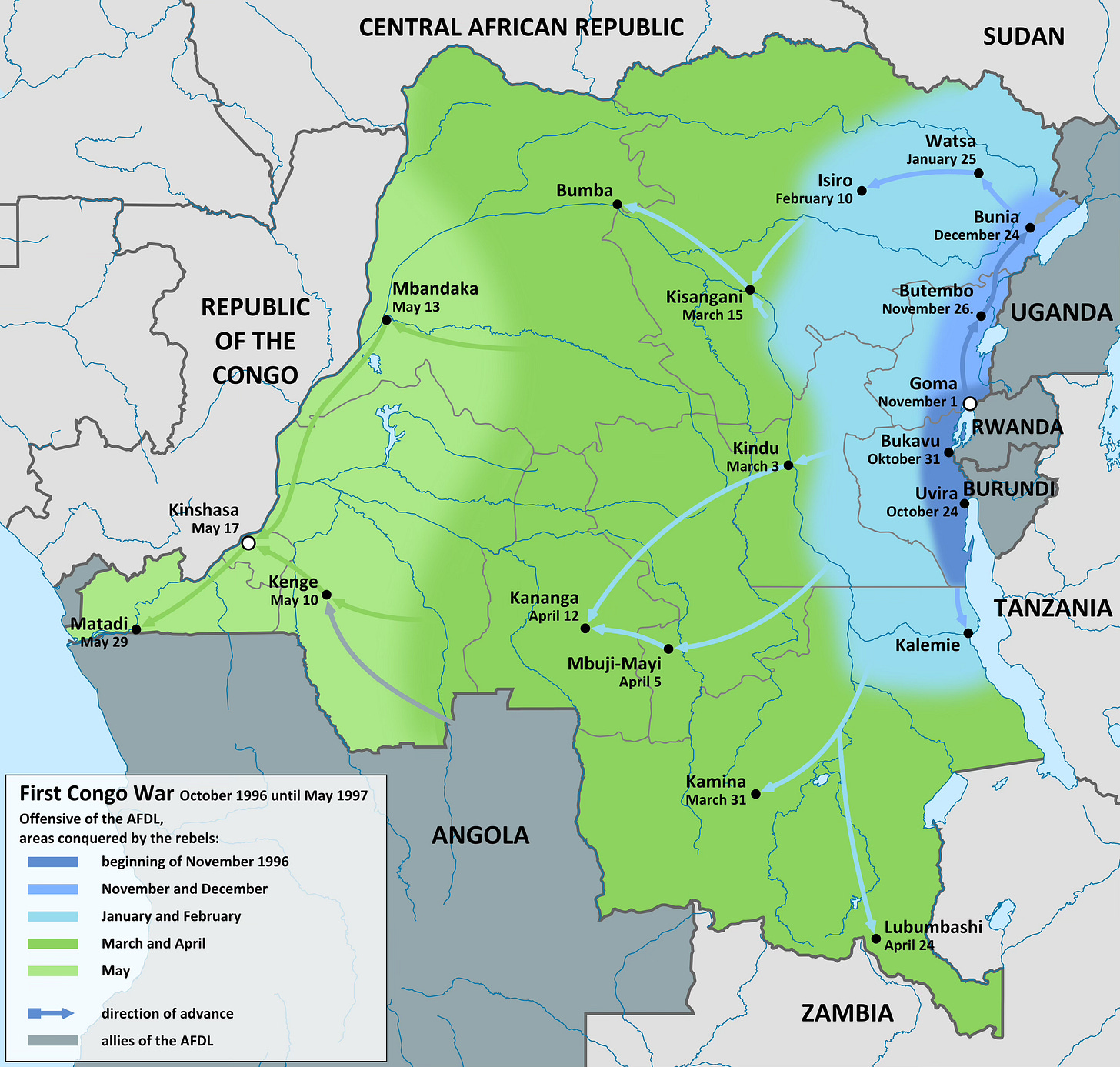

First Congo War

For over 30 years, Mobutu had allowed Zaire to deteriorate in his pursuit of enriching himself and his allies. As a result, Zaire could not defend itself when the armed resistance erupted in the fall of 1996.

The resistance movement initially consisted of Tutsis, long discriminated against in Zaire. But the person behind the movement was Paul Kagame, Rwanda's leader. Plus Kagame's old friend, Yoweri Museveni, the president of Uganda.

The bond between the two men ran deep. In the 1980s, Yoweri Museveni led a rebel army in Uganda, and among his ranks was Paul Kagame—then a young Tutsi who had fled Rwanda to escape discrimination. Rising swiftly through the rebel ranks, Kagame became a key figure in Museveni's movement.

When Museveni seized power in Uganda in 1986, Kagame and other exiled Tutsis saw their chance. From the safety of Uganda, they formed the RPF, using their newfound base to strategize and gather strength. Finally, they launched their invasion—the attack that ignited the previously mentioned civil war 1990.

So, although the opposition in Zaire initially looked like a spontaneous grassroots movement, it was orchestrated and supported by Rwanda and Uganda. The countries' supposed reason was to eliminate the Hutu extremists hiding in Zaire, who continued to pose a threat to Tutsis in the region.

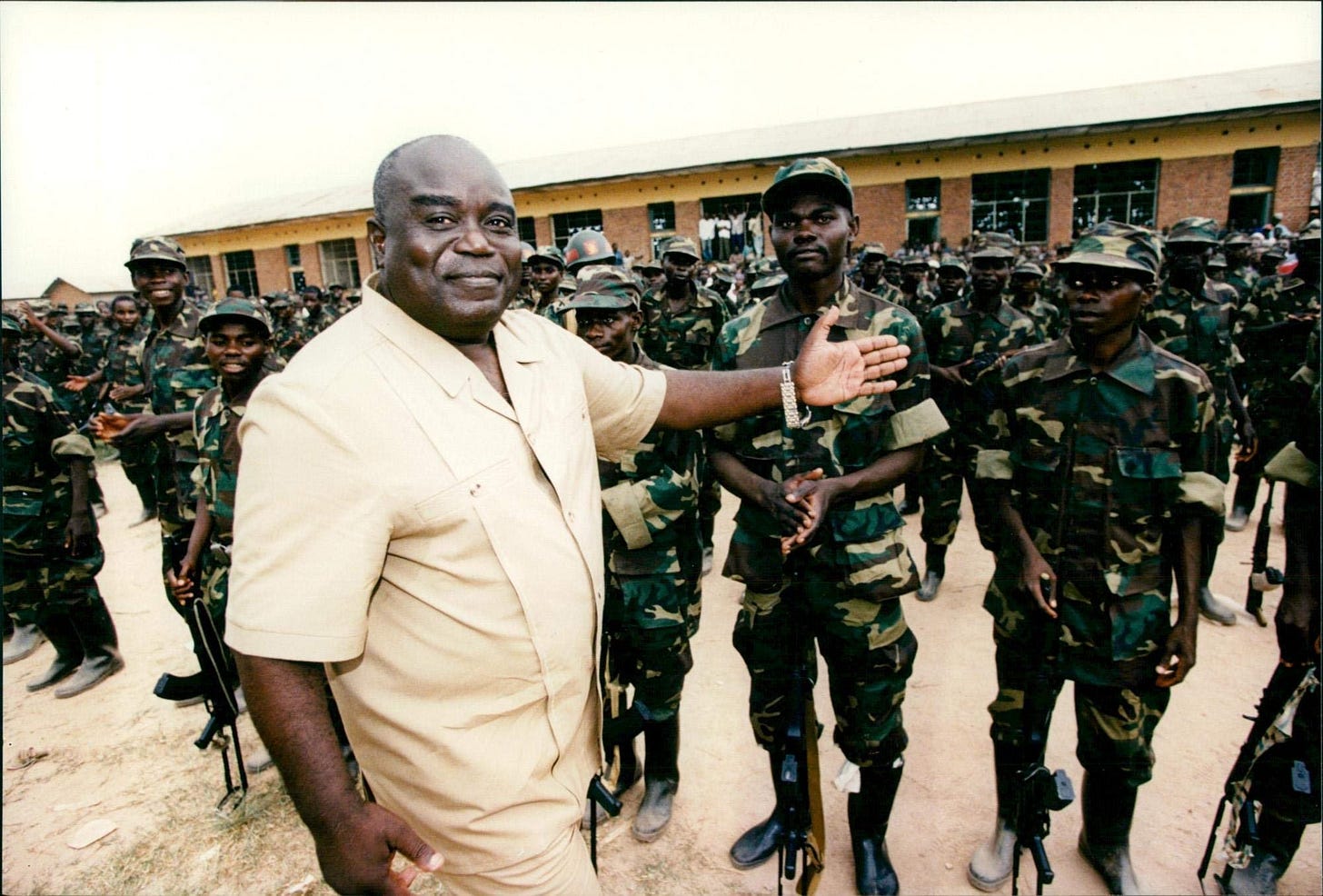

The resistance coalition was named the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo (ADFLC). Museveni wanted it to be fronted by a Zairian to make it appear less like a foreign invasion force. The choice fell on Laurent-Désiré Kabila.

Kabila – The Unexpected Leader

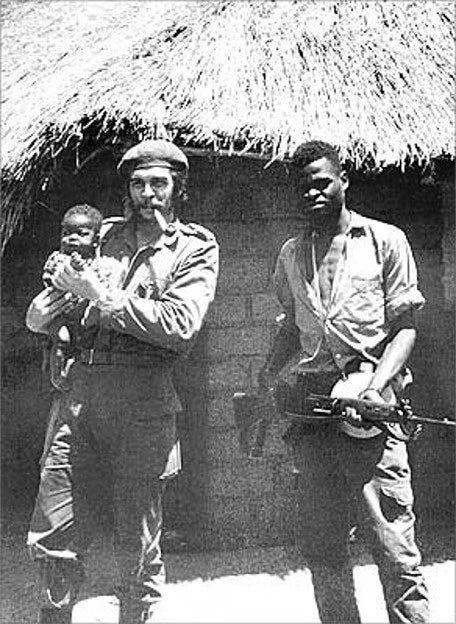

The appointment of Kabila as figurehead was unanticipated. As a former Marxist, he had already dreamed of revolt during the Congo Crisis in the 60s. For a short time during that period, Che Guevara was in the area with a small force of Cuban soldiers to foment a Marxist revolution. Kabila was one of the guerrilla leaders with whom Che Guevara allied himself.

Their alliance quickly fell apart. Kabila was more interested in alcohol and women than in preparing his troops. According to Che Guevara, he lacked "revolutionary seriousness". Since the attempted revolution failed, Kabila had made a living as a brothel owner and a gold, ivory, and timber smuggler along Lake Tanganyika. He also carved out a piece of South Kivu in eastern Zaire, which he ruled as his personal domain.

But now, in the fall of 1996, Kabila suddenly stood as leader of the ADFLC. In November, his troops took over the city of Goma in eastern Zaire. He clarified the rebels' goals before a press corps gathered in a lavish villa he had just captured from Mobutu.

The rebels would not only defeat the Hutu extremists.

They were going to overthrow Mobutu.

The ADFLC continued to blindside Zaire's ragtag defense forces – a motley crew of underpaid, undisciplined, and disinterested soldiers. Backed by Rwanda and Uganda, the rebel forces surged through villages and towns in the fall of 1996, seizing control as Mobutu ensconced himself in the opulent seclusion of his Gbadolite palace compound, far removed from the battlegrounds.

The fighting was characterized by transgressions, with both factions perpetrating heinous acts. Looting and rape became the norm. The ADFLC's advance was tainted by massacres of civilians and the conscription of child soldiers, known as "kadagos" – Swahili for "little ones." Hundreds of thousands of civilians, many of them Hutu refugees from Rwanda, were killed.

Dubbed "Africa's First World War" due to its complex web of involved parties, the ADFLC received support from Rwanda and Uganda as well as allies like Burundi, Eritrea, and Angola. In contrast, Mobutu was backed by countries like Sudan, Chad, China, and Israel. He even bolstered his troops with Serbian mercenaries from the Bosnian War and white South African soldiers of fortune.

Amidst this chaos, a geopolitical tug-of-war for Central African influence brewed, with the US and Great Britain backing English-speaking Rwanda and Uganda while France threw its weight behind Mobutu's French-speaking Zaire.

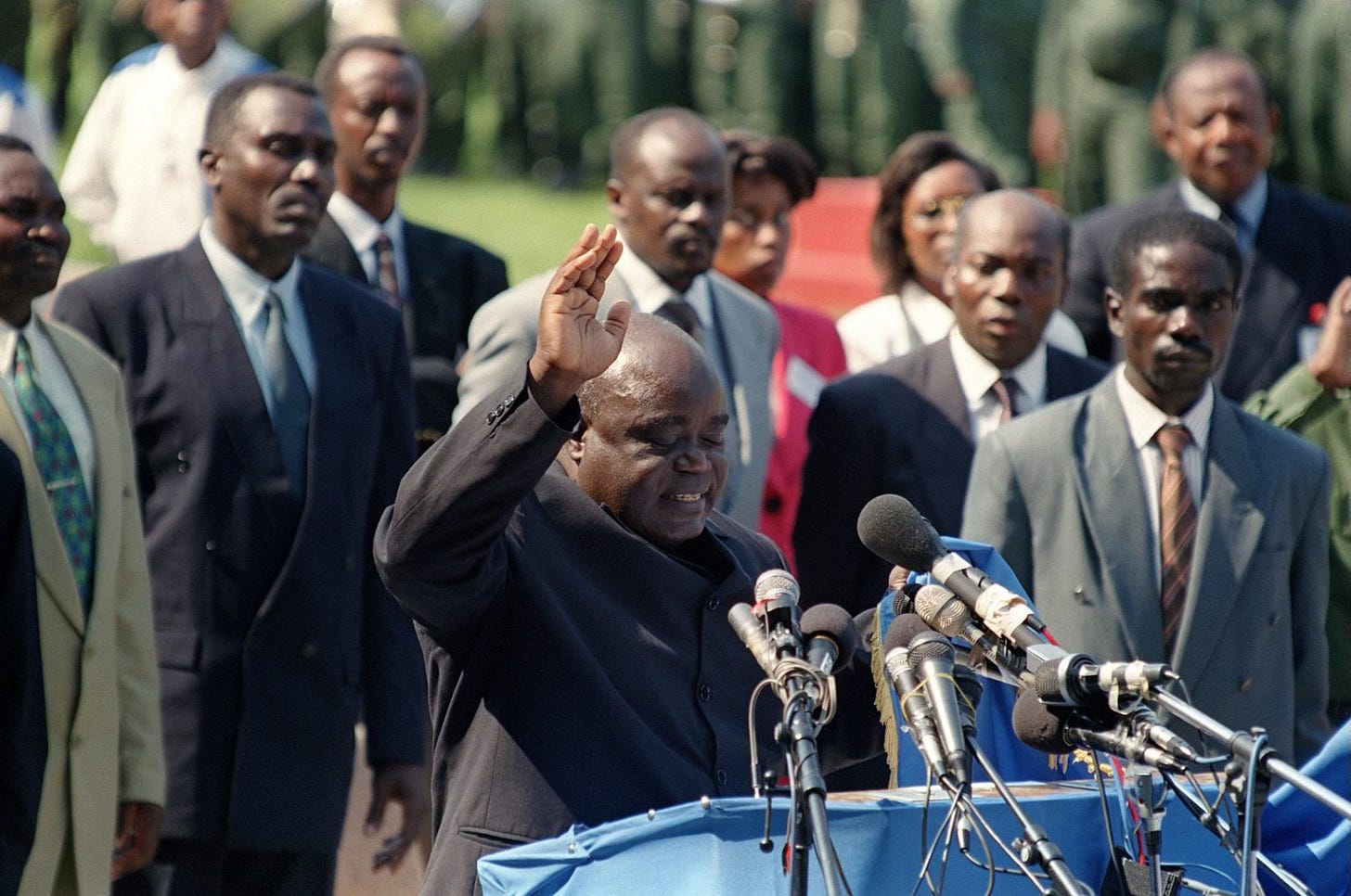

Eight months into the revolt, the capital of Kinshasa fell into rebel hands. Mobutu sought exile in Morocco, only to die of cancer four months later.

On May 17, 1997, Laurent-Désiré Kabila proclaimed himself the new president of Zaire. He reinstated the nation's pre-Mobutu identity, symbolizing a new dawn, renaming it the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Kabila was celebrated as a beacon of hope, after over three decades of Mobutu's pillaging. But the peace would last for just over a year.

Shattered dreams

Far from the harbinger of change many hoped for, Kabila's ascent heralded a continuation of authoritarianism, and his lack of political vision became swiftly apparent. After an unsuccessful career as a rebel leader in the 60s, Kabila had made a living smuggling and running brothels. A big reason why he was even chosen as the leader of the rebel movement was his linguistic prowess: he spoke English, French, Kiluba, and Swahili. But as president, he offered little.

Kabila was disinterested in power-sharing despite the Congolese populace yearning for democracy. He banned political parties, turned his back on civil society, jailed journalists and rivals, and surrounded himself with a clique of old comrades and family members, bestowing governmental positions upon them. He even used child soldiers to "keep order" in the cities. The expression "Mobutism without Mobutu" took root.

Under Kabila's leadership, corruption continued. Even before he took over, but when it was clear he was going to win, he, for example, signed an agreement with American Mineral Fields worth 1 billion dollars. The deal helped fund Kabila's rise and continued rule. In return, the mining company gained access to Congo's vast cobalt, copper, and zinc reserves.

The summer of 1997 marked a turning point in public perception as Rwanda's and Uganda's significant influence in Mobutu's ousting became apparent. This realization fostered resentment among some Congolese toward the foreign troops still in the country, who were exploiting eastern Congo's natural resources.

Attempting to shake off the image of a foreign puppet, Kabila distanced himself from his allies. He reneged on his promise to Rwanda to neutralize Hutu extremists in Congo, who continued to launch attacks against Tutsis in the region.

His decision to expel foreign troops in July 1998 further incensed his sponsors. Just over a year after Rwanda and Uganda had brought him to power, the countries plotted his downfall, setting the stage for a new, even more devastating, war.

Second Congo War

In August 1998, a new rebel group, the Rally for Congolese Democracy (RCD), attacked Kabila's government troops, beginning the Second Congo War.

The rebellion was a patchwork coalition, ranging from former Mobutu loyalists to one-time Kabila supporters, now estranged for myriad reasons. Dominated by Tutsi but heavily backed by Uganda and particularly Rwanda, the RCD swiftly captured town after town in eastern Congo. Rwanda even airlifted troops to western Congo, opening another battlefront.

Thousands of Congolese government soldiers defected to the rebels. Kabila's regime teetered on the brink, besieged and seemingly doomed.

In desperation, Kabila made an unsavory alliance with Hutu extremists. He took to the airwaves, inciting the public against Tutsis, which led to sporadic massacres and imprisonments.

But what saved Kabila was the intervention of Angola and Zimbabwe on his behalf. Chad and Namibia soon joined Kabila's cause, while Burundi sided with the rebels. What might have been a swift toppling of Kabila's rule instead spiraled into prolonged mayhem.

The motivations for these countries' involvement varied:

Fears of rebels exploiting the unstable DRC as a base.

Aspirations to expand regional influence.

The pursuit of favorable trade deals. For example, Angola gained influence over Congo's petroleum and diamond industries, while Zimbabwe secured control over a portion of a state-owned mining company.

But the overriding lure was Congo's subterranean wealth. As millions of civilians became casualties, the rampant, unabashed looting escalated.

In eastern Congo, Rwanda, Uganda, and various militias ransacked the land for its coltan, gold, diamonds, coffee – basically every valuable resource they could get a hold of. While the Congolese people faced mass atrocities, it became clear that the war, for some, was hugely lucrative.

The war's trajectory grew increasingly chaotic. Rebel factions multiplied and splintered. Alliances crumbled, and deep-seated ethnic tensions boiled over into violence. The horrors of war – massacres, torture, rape, displacement, and famine – became the grim daily reality. Millions of people died or were killed, and millions more were forced to flee.

In the summer of 1999, the involved states inked a ceasefire agreement, quickly unraveling as all sides breached it. The UN soldiers deployed to stabilize the situation could not maintain order.

By early 2001, paranoia had taken hold of Kabila. Fearing a coup, he ordered the execution of 47 kadogos (child soldiers) he had previously relied upon. The following day, a young bodyguard, once a kadogo himself, entered Kabila's office. He leaned towards Kabila as if to say something to him and then shot him dead.

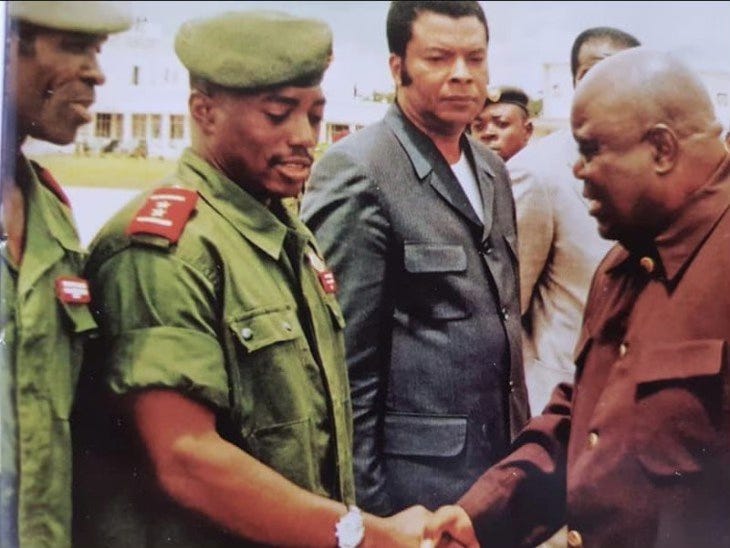

After Kabila's assassination, his supporters began discussing a successor. The negotiations were protracted, but in the end, they chose Kabila's son, Joseph.

The Pursuit of Peace

Similar to his father's, Joseph Kabila's appointment raised eyebrows. Shrouded in mystery, even basic details like his birthplace and age were matters of speculation. His political inexperience and shy demeanor fueled theories that he might be a leader in name only, manipulated by his father's seasoned party comrades.

However, before Joseph became president, he had served as Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Commander-in-Chief of the Land Forces. Thus, he had the military's support. He also proved to be surprisingly resourceful.

Kabila reversed his father's decision to ban other political parties and began talks with Congolese civil society. These efforts gradually steered the nation towards a reduction in hostilities.

A pivotal moment came when Rwanda and Uganda, implicated in a 2001 UN report for illicitly exploiting the Congo's resources, found their war efforts waning. They agreed to withdraw in exchange for Congo's commitment to neutralize and disarm the Hutu extremists involved in the Rwandan genocide and who had taken refuge in eastern Congo ever since.

In the summer of 2002, the parties signed official peace agreements. An interim government took over the following year, with Joseph Kabila as president. After delays and several setbacks, it would lead Congo to elections in 2006 – the first relatively free elections in over 40 years.

However, the impact of the nearly five-year-long war was devastating. It claimed over three million lives, most lost to starvation and disease. Millions were displaced, and the extent of sexual violence was staggering. Survivors, bearing deep physical and psychological scars, faced the daunting task of rebuilding their communities.

But despite the peace treaty and the relative stability in western Congo, the east continued to be plagued by violence. More than gold and copper, other minerals critical to the burgeoning global technology sector would perpetuate the suffering.

What's going on now?

The reasons for the continued violence in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo are highly complex: ethnic tensions, a pursuit of regional dominance, inadequate infrastructure, rampant corruption, staggering unemployment, and a central government struggling to assert authority over an expansive nation.

In addition, the country currently has over a hundred armed militia and rebel groups ranging from small, local militias to large, sophisticated organizations with international backing. Two of the biggest are the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), an Islamist group with alleged links to IS, and the re-emerged M23, previously subdued in 2013.

Yet, the crux of the enduring conflict lies in the exploitation of Congo's natural resources. Already during the Second Congo War, Rwanda, Uganda, and various rebel leaders plundered the country for raw materials. During that period, Rwanda and Uganda's coltan exports spiked despite the countries themselves having small coltan reserves.

This pattern of plunder persists, with rebel groups orchestrating the looting and funneling these resources to international companies in the West, China, and the Middle East through intermediaries like Rwanda.

This illicit trade bankrolls the rebels' ongoing warfare. Among the coveted resources are gold, cassiterite, tungsten, tin, and coltan, essential for laptops, mobile phones, and gaming consoles. Congo also has the world's largest reserves of cobalt, the mineral used in batteries and a key factor in determining whether the electric vehicle revolution will truly take off.

According to a recent Congolese lawsuit, well-known tech giants like Apple are profiting from the misery. In December 2024, Congo filed a complaint in which the country, in broad terms, accuses the company of trying to hide the use of "blood minerals" in its supply chain—minerals extracted under difficult or forced conditions in areas characterized by violence and human rights violations.

Apple has denied the allegations, and it will take a long time before the investigation is completed and the case is eventually cleared up. But the fact that Congolese minerals, extracted through child and forced labor, appear in the supply chains of many international companies is indisputable.

From the onset of the First Congo War in 1996 to the present hostilities, the conflict has claimed up to six million lives, standing as the deadliest global war since World War II.

Even as of writing, and despite a large UN peacekeeping mission, eastern Congo is marred by kidnappings, sexual violence, the use of child soldiers, massacres, and assaults on refugee camps. 13 international peacekeepers were killed in M23:s latest offensive on Goma and up to 7 million people are currently internally displaced.

Whether the international community will heed Congo's call and take action against Rwanda remains an open question. After all, sanctions on Rwanda were key in defeating M23 in 2013.

Or will Rwanda's carefully cultivated pro-Western image—bolstered by a willingness to accept asylum seekers from Europe—now shield it from any real consequences?

Further reading:

”Post-Independence Politics in the Congo” by Merwin Crawford Young in Transition (nr 26, 1966)

”The Recourse to Authenticity and Negritude in Zaire” by Kenneth Lee Adelman in The Journal of Modern African Studies (vol. 13, nr 1, 1975)

”The C.I.A. and Lumumba” by Madeleine G. Kalb for New York Times (August 2, 1981)

The Political Economy of Third World Intervention: Mines, Money, and U.S. Policy in the Congo Crisis by David Gibbs (1991)

The Rise and Fall of Patrice Lumumba: Conflict in the Congo by Thomas R. Kanza (1994)

”Officials Told to Avoid Calling Rwanda Killings ’Genocide’" by Douglas Jehl for New York Times (June 10, 1994)

The Rwanda Crisis: History of a Genocide by Gérard Prunier (1995)

"U.S. Firms Stake Claims In Zaire's War" by Cindy Shiner for Washington Post (17 april, 1997)

”Anatomy of an Autocracy: Mobutu’s 32-Year Reign” by Howard W. French for New York Times (May 17, 1997)

”Kabila sworn in as president of Congo" by CNN (May 29, 1997)

We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed with Our Families by Philip Gourevitch (1998)

The Assassination of Lumumba by Ludo De Witte (2001)

When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda by Mahmood Mamdani (2001)

The Congo: From Leopold to Kabila: A People’s History by Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja (2002)

The History of Congo by Ch. Didier Gondola (2002)

The African Stakes of the Congo War by John F. Clark (editor) (2004)

The State of Africa: A History of the Continent Since Independence by Martin Meredith (2005)

Life Laid Bare: The Survivors in Rwanda Speak by Jean Hatzfeld (2007)

Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA by Tim Weiner (2007)

The Congo Wars: Conflict, Myth and Reality by Thomas Turner (2007)

Lumumba: Africa’s Lost Leader by Leo Zeilig (2008)

“Kagame’s Hidden War in the Congo” by Howard W. French i New York Review of Books (September 24, 2009)

Congo: The Epic History of a People by David Van Reybrouck (2010)

”A second Rwanda genocide is revealed in Congo" by Michelle Faul for Associated Press (10 oktober, 2010)

Death in the Congo: Murdering Patrice Lumumba by Emmanuel Gerard and Bruce Kuklick (2015)

"New Insights on Congo's Islamist Rebels" by Daniel Fahey for Washington Post (February 19, 2015)

Do Not Disturb: The Story of a Political Murder and an African Regime Gone Bad by Michaela Wrong (2021)

"Congo’s Gold Curse Continues" by Moses Sawasawa for Congo in Conversation (May 5, 2021)

”Tshisekedi calls out Kagame on the M23 militia" by Africa Confidential (July 7, 2022)

"Revived M23 rebellion worsens DR Congo’s security troubles" by Claude Sengenya and Patricia Huon for New Humanitarian (July 7, 2022)

"DR Congo: Atrocities by Rwanda-Backed M23 Rebels" by Human Rights Watch (February 6, 2023)

”Conflict in eastern DR Congo flares again" by Paul Lorgerie and Mimi Mefo Takambou for Deutsche Welle (October 25, 2023)

”Conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo" by Center for Preventive Action (October 31, 2023)

”International peacekeepers killed as fighting rages around eastern Congo’s key city” by Justin Kabumba and Mark Banchereau for Associated Press (January 26, 2025)

"Rwanda, the West’s ‘Donor Darling,’ Seizes an Opportunity in Congo" by Ruth Maclean for New York Times (January 28, 2025)