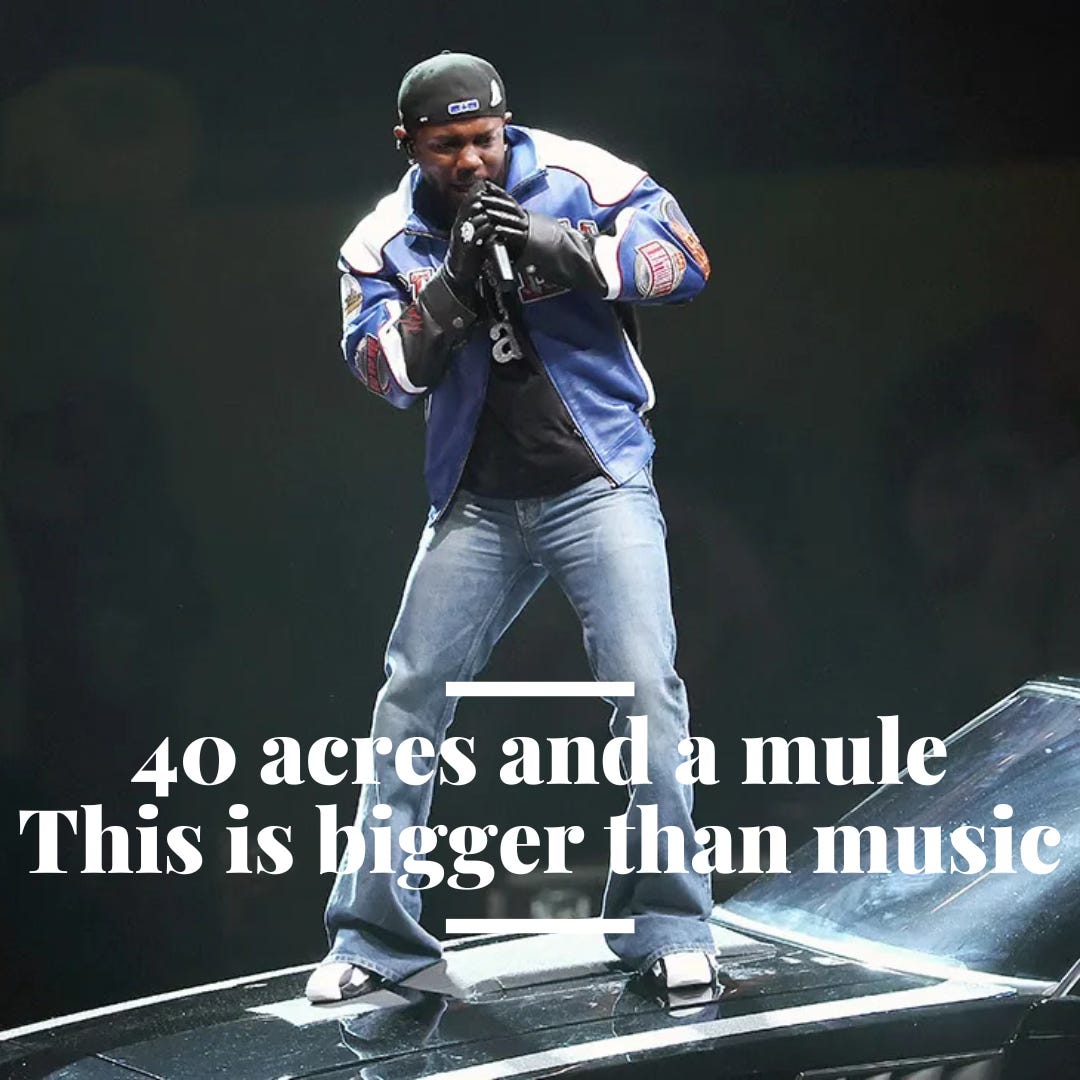

What's the meaning behind 40 acres and a mule?

Kendrick Lamar's Super Bowl performance raises questions

Those who watched Kendrick Lamar's Super Bowl performance might have caught his reference to 40 acres and a mule. But what does that phrase actually mean?

Since at least the 18th century, Black Americans had pushed for reparations for their stolen labor, but the debate gained serious momentum in the 1860s as slavery was abolished.

And the idea of compensation wasn't outlandish. Many nations had already paid large sums of money to their former slaveowners as compensation for the loss of their so-called "property" when slavery was abolished.

This approach, known as compensated emancipation, was implemented in countries such as Denmark, Brazil, the Netherlands, Argentina, and Colombia.

As part of the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 and the Slave Compensation Act of 1837, Britain also agreed to pay around £20 million to enslavers across its colonies. The country took a bank loan amounting to over 40 percent of the British Treasury's annual spending to finance the compensation.

Due to its structure, the loan wasn't fully repaid until 2015—nearly two centuries later. Research from University College London, which analyzed 46,000 transactions, revealed that the beneficiaries of this compensation weren't just aristocrats and plantation elites; they also included ordinary British citizens and prominent families who used the money to invest in businesses, real estate, and political careers.

As mentioned in the podcast series about the Haitian Revolution, France imposed one of the most devastating financial burdens in history. After Haiti's successful revolution against French rule, France forced the newly independent Black Republic to pay reparations for lost "property"—a debt that drained Haiti's economy for over a century and wasn't fully paid off until 1947.

The U.S. also experimented with compensated emancipation. In 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act, which freed more than 3,000 enslaved people in Washington, D.C. However, instead of compensating the formerly enslaved, the U.S. government paid $300 per freed person—to their former owners. In total, the state paid out nearly $1 million (equivalent to over $25 million today).

Enslaved people, in some cases, were eligible for $100 in compensation, but only if they agreed to leave the country and relocate to Haiti or Liberia—a policy that underscored how much of the U.S. government's approach to emancipation was shaped by the idea that freed Black people didn't truly belong in America.

"40 Acres and a Mule"—A Promise Made and Broken

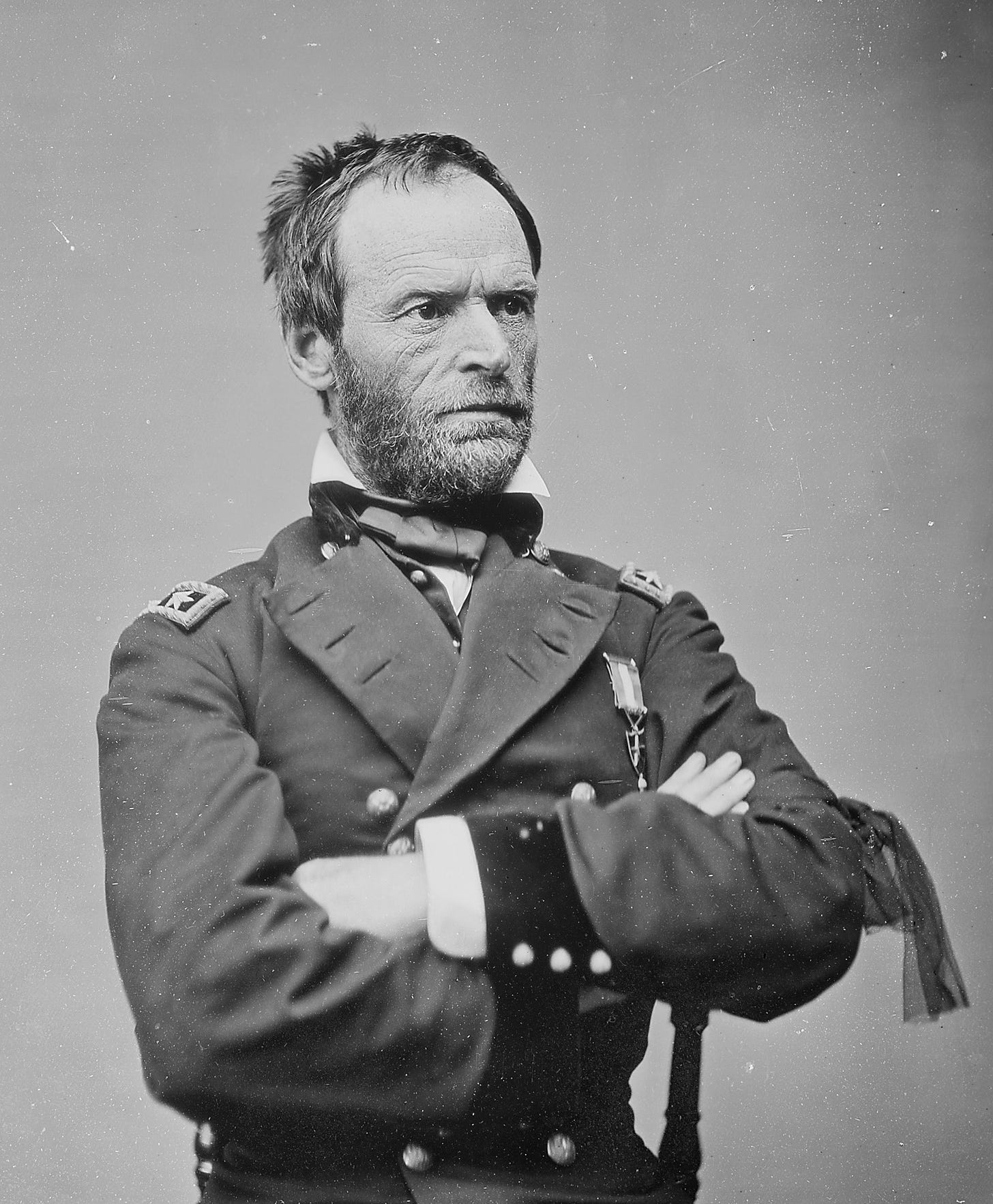

In January 1865, as the Civil War raged on, Union General William Tecumseh Sherman and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton met with 20 Black Baptist and Methodist pastors in Savannah, Georgia. They asked the pastors what newly freed Black people needed most to secure their future. The group's spokesperson, Garrison Frazier, responded with: land.

A few days later, Sherman issued Special Field Orders No. 15, which designated 400,000 acres of coastal land across South Carolina, Georgia, and northern Florida for redistribution to freed Black families. Each family would receive up to 40 acres. Sherman later amended the order to include army mules to help cultivate the land.

Lincoln supported the decision, giving hope to Black Americans. For the first time, it seemed that they might receive the resources to build independent, self-sustaining lives. In a nation where landownership was the foundation of wealth, the promise of 40 acres and a mule had the potential to fundamentally reshape the economic future of Black Americans.

But that promise was short-lived.

Abraham Lincoln was assassinated in April 1865, and his successor, Andrew Johnson, had little sympathy for the cause of Black land ownership. By the fall of 1865, he rescinded Sherman's order, effectively stripping thousands of freedmen of the land they had already begun to cultivate.

The land was returned to its original white owners. In many cases, the U.S. Army forcibly removed Black families from their homes. Those who had briefly tasted the possibility of landownership were left landless and economically stranded.

The Consequences of Broken Promises

Because Black Americans were never compensated for their stolen labor, they began their new era of freedom at a severe disadvantage. They lagged behind in everything from income and education to property and access to healthcare.

In the South, Jim Crow laws were introduced in the 1870s, which legally codified segregation. In the North and West, racism was often less overt but still destructive, manifesting in hiring discrimination, exclusion from housing markets, and limited access to public services.

A Legacy Stretching Beyond the U.S.

The pattern of economic exclusion and racial discrimination that followed emancipation wasn't unique to the United States.

Across South America, Black populations in countries like Brazil, Colombia, and Venezuela— forcibly brought to the continent through the transatlantic slave trade—faced similar post-slavery struggles. Though slavery ended, systemic barriers kept Afro-descendant communities in conditions of poverty, exclusion, and limited opportunity.

This historical reality is precisely what Martin Luther King Jr. addressed when he sat down with NBC News' Sander Vanocur in 1967, less than a year before he was assassinated. In the interview, Vanocur asked King why Black Americans, in particular, had struggled to "pull themselves up by the bootstraps."

King's response was clear: how can people be expected to lift themselves up when they were never given boots in the first place?

What If the U.S. Had Kept Its Promise?

The phrase 40 acres and a mule represents a radical proposal and one of American history's greatest "what ifs." Had the U.S. government followed through on land redistribution, Black Americans could have secured some of the same opportunities that white Americans enjoyed through programs like the Homestead Act and New Deal housing policies. Which Black people were technically eligible for, but again, due to discriminatory practices, were largely shut out.

Instead, the racial wealth gap persists. White families, on average, hold nearly 10 times the wealth of Black families.

Had America reckoned with its history differently, perhaps some of today's stark racial inequalities—especially in wealth, homeownership, and economic opportunity—could have been avoided.

But history does not move backward. The question now is: how does a country make amends for a debt it never paid?

Lamar's reference to this historical injustice on America's largest stage, and with the president in the audience, should not be underestimated. Especially in times when the country's Republican politicians are making every effort to limit or distort the teaching of Black history in schools.

Further reading:

Books:

The Civil War and the Constitution, 1859–1865 by John William Burgess (1901)

The Price of Emancipation: Slave-Ownership, Compensation and British Society at the End of Slavery by Nicholas Draper (2009)

Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861–1865 by James Oakes (2013)

Articles:

”Britain’s colonial shame: Slave-owners given huge payouts after abolition” by Sanchez Manning for The Independent (February 24, 2013)

”Uncovering Britain’s hidden links to slavery” by UCL News (February 25 , 2013)

”The treasury’s tweet shows slavery is still misunderstood” by David Olusoga for The Guardian (February 12, 2018)

”Britain’s Slave Owner Compensation Loan, reparations and tax havenry” by Naomi Fowler for Tax Justice Network (June 9, 2020)