"Perhaps, in the future, there will be some African history to teach. But at present there is none, or very little: there is only the history of the Europeans in Africa."

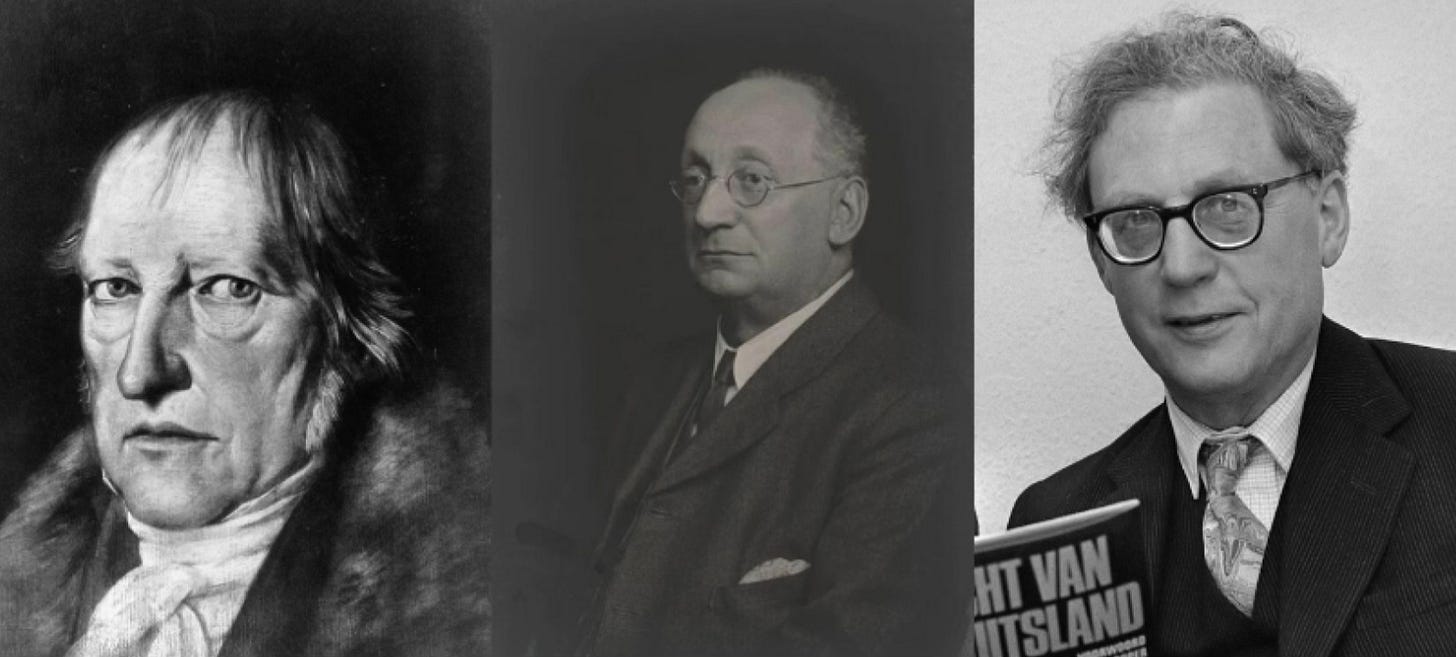

In the introduction to the 1965 book The Rise of Christian Europe, the English historian Hugh Trevor-Roper lamented the trend of students thirsting to learn more about "the history of Black Africa" beyond classical stories about the pharaohs of Egypt and the campaigns of Carthage. Roper was a history professor at Oxford University, known for the 1947 bestseller The Last Days of Hitler.

He continues:

"If all history is equal, as some now believe, there is no reason why we should study one section of it rather than another; for certainly we cannot study it all. Then indeed we may neglect our own history and amuse ourselves with the unrewarding gyrations of barbarous tribes in picturesque but irrelevant corners of the globe: tribes whose chief function in history, in my opinion, is to show to the Present an image of the past from which, by history, it has escaped."

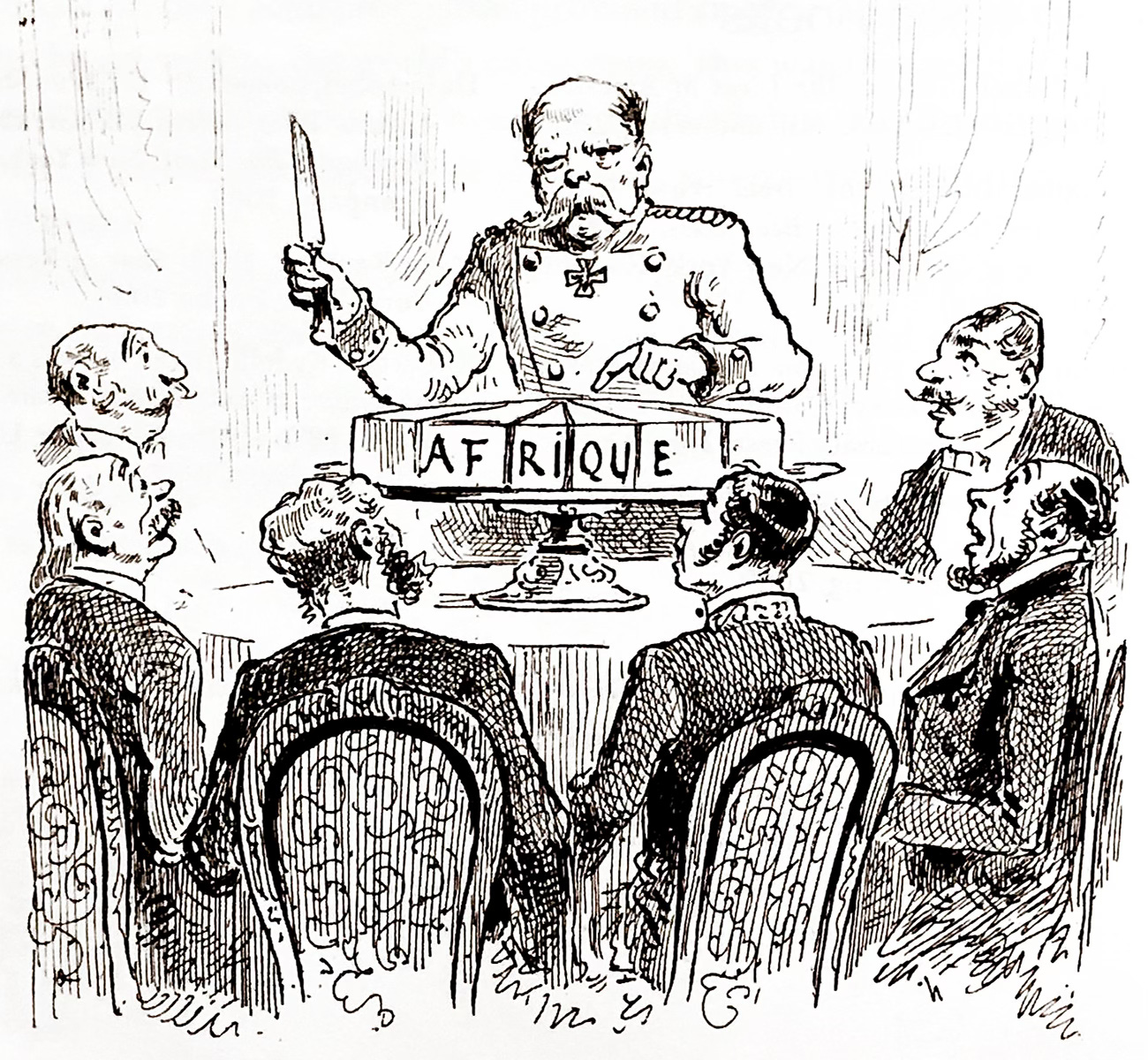

Trevor-Roper's statement represented much of the Western world's view of sub-Saharan Africa, still heavily marked by colonialism and, before that, centuries of slavery.

More than a hundred years earlier, the famous German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel had demonstrated similar lines of thought. In Lectures on the Philosophy of History from 1837, he writes that black Africans represent man in his "wild and untamed form." Hegel argued that the lack of self-control made progress and the creation of a culture impossible:

"At this point we leave Africa, not to mention it again. For it is no historical part of the world; it has no movement or development to exhibit. Historical movements in it—that is in its northern part—belong to the Asiatic or European World."

The 19th-century British colonial administrator Henry Bartle Frere concurred:

"If you read history of any part of the Negro population of Africa, you will find nothing but a dreary recurrence of tribal wars, and an absence of anything which forms a stable government, and year after year, generation after generation, century after century, these tribes go on obeying no law but that of force, and consequently never emerging from the state of barbarism in which we find them at present, and in which they have lived, so far as we know, for a period long anterior to our own."

British Arthur Richards, who served as governor of The Gambia in the 1930s and Nigeria in the 1940s, was similarly convinced of the perpetual stagnancy of Africa:

"For countless centuries, while all the pageant of history swept by, the African remained unmoved — in primitive savagery."

In 1930, the British ethnologist Charles Gabriel Seligman published his theories about Africa's so-called races. He was talking about race in a biological sense. He classified one of them – the Hamites – as a subgroup of the Caucasian race. He proposed that it had immigrated from outside and settled in North and East Africa.

According to proponents of this so-called Hamitic hypothesis, Africa had the Hamites to thank for all the development on the continent. Everything from ancient Egypt's pyramids to Ethiopia's churches belonged to the European or white sphere. Seligman's book The Races of Africa remained in print until 1979.

People like Hegel, Seligman, and Trevor-Roper were not the equivalent of Internet trolls. They were elevated intellectuals whose words set the tone for ideas about how the world worked. The thought that Black Africa, as it is often called, has no history was a dominant Western view well into the 1960s.

For many thinkers of the time, human development was a bit like the classic computer game Civilization. In this game, you choose a known civilization and take it from the Stone Age into our time by following predetermined paths of technological discovery: first the wheel, then writing, and so on.

For Trevor-Roper, Hegel, Seligman, and many others, history was an ever-advancing and conscious movement, with Western civilization being the latest, most advanced stage and African civilization the first, most primitive. Africa was only interesting to show what uncivilized and barbaric traditions and ways of life the West had long since left behind.

This view created a cycle – as Africa was largely considered devoid of history worth studying, few attempts were made to study it, resulting in few discoveries. Archeology was characterized by similar patterns, contributing to few excavations.

But it wasn't just ignorance born of a belief in superiority. In A History of Modern Africa: 1800 to the Present, first published in 2009, the English historian Richard J. Reid writes that there were also active attempts to trivialize, co-opt, or erase African history during the colonial period.

In Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, for example, the colonial administration censored archaeological finds pointing to Great Zimbabwe's impressive ruins being built by black Africans. Instead, a theory was preferred that ancient Phoenician colonizers from present-day Lebanon erected it. This misinformation and censorship continued well into the 1970s. That's practically yesterday.

Similarly, the myth was spread that what is today South Africa consisted of "empty land” before the Europeans arrived, a myth designed to give the colonizers the same right to the land as the indigenous people they displaced. Although the theory has been disproved, versions of it continue to appear in South Africa even today, especially amongst far-right groups, to legitimize why descendants of Europeans still own the majority of the land, even though they are a minority.

With the African independence movement in the 1950s and 1960s, historians began to show more interest in pre-colonial African history. Significant progress has been made since then, but the view that dominated for so long has left its mark.

In Western academia, interest in African history began to surge during the 1950s and 1960s, coinciding with the wave of independence sweeping across the continent and the newfound optimism about Africa's future.

Until then, historical narratives had largely been shaped by imperialist perspectives—stories where Europeans, often depicted as daring adventurers or powerful men, took center stage, relegating Africans to mere background figures. The shift in focus brought a desire to explore Africa's pre-colonial past, seeking clues about what a self-governing Africa might look like.

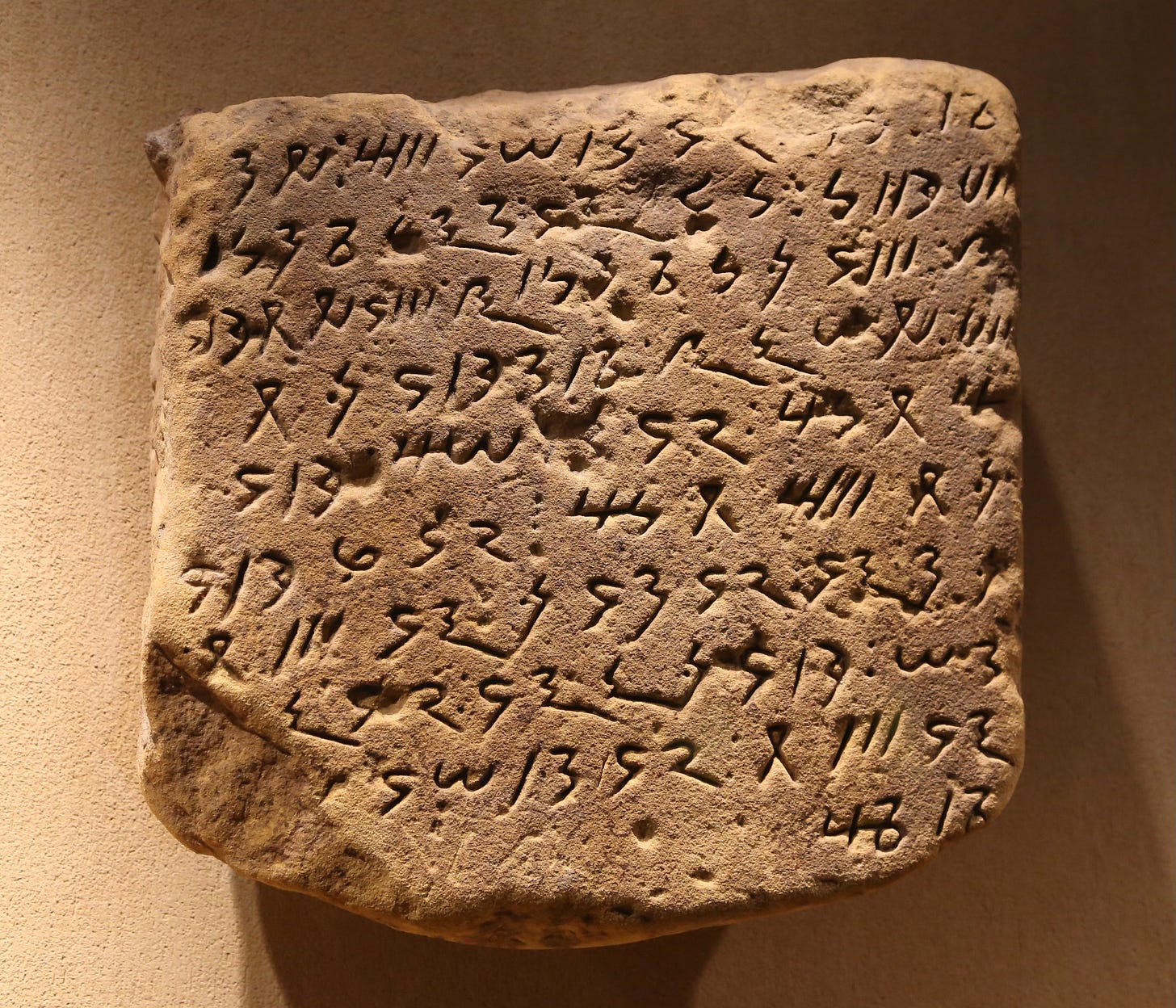

But in historical science, primary sources—original sources from the time period being studied—have always been crucial. This created problems because many African countries lacked pre-colonial written languages.

However, the emphasis on primary sources—original materials from the time being studied—posed significant challenges for historians. Many African societies lacked pre-colonial written languages, relying instead on oral traditions. The oral tradition was indeed rich, but historians of the time often considered it unreliable at best and useless at worst.

Much of what we know about early African history has come from archaeological discoveries, linguistic studies, and the written accounts of foreign visitors. These include Arab explorers who visited West Africa during the Middle Ages and European missionaries who sought to spread Christianity from the 16th century onward.

While these accounts provide valuable insights, they are riddled with biases—racism, condescension, and reductionism are all too common.

By the 19th century, as Europeans explored Africa's interior, their written records often revealed an unsettling arrogance. Many seemed to genuinely believe they were the first to "discover" the continent's rivers, mountains, and lakes, viewing the African people they encountered not as equals but as mere extensions of the landscape, no different from the wildlife.

With a lack of indigenous pre-colonial sources, much of the historical focus shifted to colonial history. The opening of colonial archives after independence offered historians abundant written material to work with.

However, this focus was further reinforced by practical challenges: economic and political crises in the 1970s and 1980s made fieldwork in Africa challenging for foreign scholars while local academics grappled with dwindling university funding.

One consequence of the dominance of colonial history is that the image of Africa as a continent whose story begins with the arrival of Europeans – the image propagated by Trevor-Roper, Hegel, and Seligman – has survived to this day. A quick Google search of "Why is Africa…" reveals autocomplete suggestions like "so underdeveloped," "so poor," and "so far behind."

There are still those who see Africa as more or less the same country, a dark corner of the world dominated by endless wars and widespread poverty, or even those who think that the continent owes its progress to colonialism.

This widespread misconception is precisely why I've dedicated the past seven years to bringing attention to this overlooked part of world history. Contrary to common stereotypes, Black history has profoundly shaped the modern world.

As you've noticed, I use "Black History" rather than "African History". The reasons are several.

Firstly, I don't just focus on the history of Africa. Here, you'll read stories from everywhere Black people have their history: Africa, Europe, North and South America, the Caribbean, the Middle East, and even East Asia.

Secondly, there are different opinions about what Africa means. Geographically, it's simple: the landmass stretches from Cape Verde to Mauritius, from the Mediterranean to South Africa.

But it immediately becomes murkier from a historical, political or cultural perspective. Different historians include North Africans when writing about African history, and others only include Black Africans.

The same problem arises when talking about people belonging to the "African diaspora" – should they be included in the study of African history? And if so, who? Most people can probably agree that African Americans are part of African history, but should France's many residents with backgrounds in Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia also be incorporated?

In navigating issues like these, it is worth remembering that concepts like "Europe" and "Africa" are artificial constructs. The concept of Europe, for example, has existed for millennia, but its meaning has evolved over time. And just as a medieval person living in what we now call Germany did not see himself as European, people in Africa did not identify as African until relatively recently.

"Black" is similarly an artificial construct. It's not an uncomplicated term and can be perceived differently depending on time, place, and culture. A person who would be perceived as Black in the U.S. may be considered mixed in Brazil. A person from Sudan who would be interpreted as Black in Europe may identify as Arab.

I still use the term" Black" for the simple reason that most people today, even on a global scale, have a fairly similar idea of what it means. I believe it provides a useful starting point for understanding the histories I explore.

But for the sake of clarity, the" Black" in Black History Unveiled refers to the African population south of the Sahara and the enormous diaspora that has its roots in this vast part of the world.

Some may wonder if this approach isn't backward. What do we really gain by lumping together such different countries as Ethiopia and the Democratic Republic of Congo under the term "Black history"? But the various cultures I write about actually do have a common denominator: they have historically been bundled together and considered insignificant precisely because they involve Black people. By uncovering these overlooked narratives, I hope to shed light on their unique qualities while assembling a fuller picture of the past.

Through this project, I strive to provide nuance to Black history. When addressing topics like war, poverty, slavery, or colonialism, my goal is not to dwell on suffering but to contextualize these events, explain their origins, and illuminate their enduring effects.

Equally important is sparking curiosity about the wealth of knowledge that exists. Despite early African historiography's challenges, recent decades have seen tremendous progress. I regularly share resources for deeper exploration—not as a historian presenting groundbreaking research but as a bridge connecting people to the invaluable work of scholars.

That's how I can best use my skills as a journalist. So make no mistake: this project would not be possible without the passionate and meticulous work of the researchers.

The goal of Black History Unveiled is not to pose as an expert or to claim I have all the answers; the goal is just to make a small contribution to increasing people's interest in this topic.

There will always be more to say than what can fit in these articles, but I hope I can spark some curiosity or maybe show people where they can learn more about Black history.

Many writers, historians, podcast creators, and activists have similar missions. Hopefully, the collective effort can make a difference.

Further reading:

Lectures on the Philosophy of History by Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1881)

"Archaeology in Africa" by Basil Davidson in The Atlantic (April, 1959)

The Rise of Christian Europe by Hugh Trevor-Roper (1965)

”Toward a Theory of Black African Civilizations: The Problem of Authenticity” by Hanes Walton, Jr. in Journal of Black Studies (vol. 1, nr 4, June, 1971)

”African History: Unrewarding Gyrations or New Perspectives on the Historian’s Craft” by A.J.R. Russell-Wood i The History Teacher (vol. 17, nr 2, 1984)

”Negro, Black, Black African, African Caribbean, African American or What? Labelling African Origin Populations in the Health Arena in the 21st century” by Charles Agyemang, Raj Bhopal and Marc Bruijnzeels in Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health (vol. 59, nr 12, 2005)

”The Falsity of Hegel’s Theses on Africa” by Babacar Camara in Journal of Black Studies (vol. 36, nr 1, 2005)

”Past and Presentism: The ’Precolonial’ and the Foreshortening of African History” by Richard J. Reid in The Journal of African History (vol. 52, nr 2, 2011)

A History of Modern Africa: 1800 to the Present by Richard J. Reid (2012)

The Civilizations of Africa: A History to 1800 by Christopher Ehret (2016)

Africans: The History of a Continent by John Iliffe (2017).